Go ahead, stare

After a traumatic brain injury, raw self-portraits give an artist power over her disability

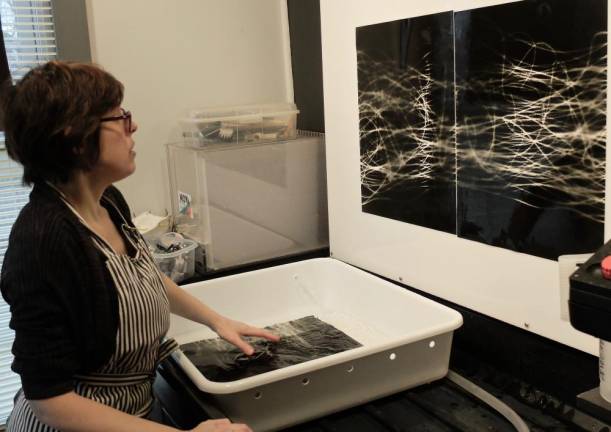

In the dim amber safelight, Claire Gilliam moves around the darkroom with assurance. She’s making a print, part of Life Lines, her most recent series of photograms and etchings.

Instead of placing a camera negative into the enlarger, she secures a pencil drawing done on transparent vellum over a sheet of photographic paper. She exposes it to light for a couple of seconds.

“It’s magic, isn’t it,” she says gleefully, slipping the exposed sheet into the tray of developing chemicals. Thick interwoven strands, some in focus, some not, emerge in shades of black, gray and white. Squinting in the low light, Gilliam finds the tone she’s looking for and transfers the print to the stop bath, preventing it from developing further.

Gilliam, a British-American artist who lives in Warwick, has been honing her skills in the darkroom since her days at Sheffield Hallam University in the UK, where she earned a BA in Fine Art in the late 90s. Professors told Gilliam to think of concept – to formulate an idea into a visual. They encouraged her to use her body to tell a story: a photo self-portrait, a handprint turned into an etching. She experimented in the darkroom and the print studio, but was not yet sure what she wanted to say. She was drawn to performance art, to artists whose bodies were central to their narrative.

“The idea of how you see yourself is often very different from how others see you,” Gilliam says. That was the idea she was interested in exploring.

Gilliam shifts the print to the tray of fixer, then a water bath to rinse it. Turning on the light in the darkroom, she carries the print to the bright side of her workroom where she mounts it on the wall, adhering it to a glass plate.

Before starting her graduate studies, Gilliam came to the U.S. to do a week’s course with fine art photographer Arno Minkkinnen at Maine Media Workshops. She fell in love with the place, the openness of the people, and the enthusiasm of her teacher. On a whim, she signed up to do a certificate program at Rockport College to learn the in-depth craft of photography and printing. “They really pushed you to think about the personal in your work,” she says, which she found a refreshing change from the conceptual approach of her English training. The die was cast.

Gilliam stands back to study the fresh print. Where are the eyes drawn? Does it have contrast and tonality, provoke the senses, the emotions, stimulate curiosity?

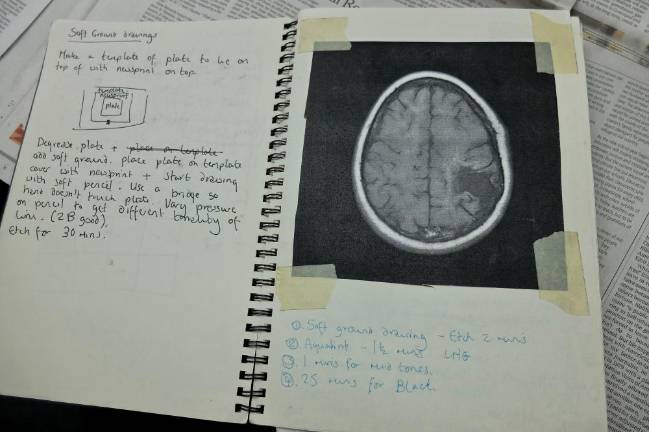

Life Lines began as a drawing project. A few years ago, Gilliam had an MRI done of her brain. “The scans, which I spent hours poring over, both fascinated and horrified me,” she says. In a car accident as a baby, her parents and sister were killed. Her injuries were so extensive her grandparents did not know if she would recover.

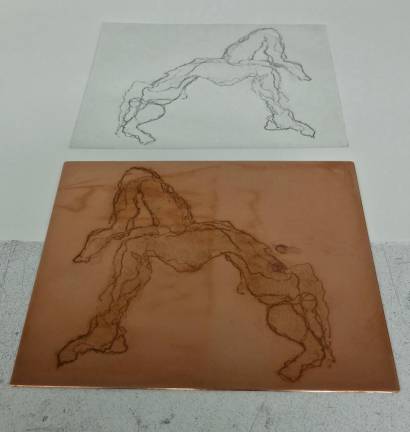

Her response to the MRIs was to make drawings of the brain to untangle its structure and pathways – how they shape who we become. “Even though I’d always known the seriousness of it, I was suddenly confronted with visual evidence of the long-ago but significant brain injury I’d sustained.”

She had recently rediscovered her love of drawing as an assistant to the photographer Barbara Mensch, her friend and mentor, with whom she co-teaches at the International Center of Photography. She couldn’t verbalize what she was doing, but gradually her drawings became more and more abstract. “It felt like I was seeing the same patterns out in the environment and in nature. For me it became less about the solid body and more about the connections between things.”

Gilliam describes herself as a spontaneous artist, leaving herself open to chance, preferring to rely on intuition rather than preconceived ideas of where she’s going. That first cold winter in Maine, her professor gave her a photographic project to work on. Limited by the weather and the lack of a car to get around in, she embraced those limitations and turned the camera on herself. Using her Nikon 35mm, a tripod and timer, and a slow shutter speed, she created ghostly images of herself walking down an old corridor.

Gilliam’s injury left her with little dexterity on her right side. After struggling for years with equipment designed for the right-handed, she found a solution to her technical challenges. While living and working in Maine, Gilliam met Gene Lynch, a fellow photographer. They fell in love and eventually married, moving to Warwick in the early 2000s. Lynch gave her a Hassleblad, a medium format, high-resolution camera.

At first Gilliam was intimidated by it, but took it with her to a workshop in Maine with fine art photographer John Goodman. “This camera was brilliant once I lost my fear of it,” she says. “I could hold it and press the shutter release with my left hand, which I’d never been able to do before.” Goodman encouraged her to take chances with the new camera, to think outside the box, only this time, take her clothes off!

The idea of photographing herself nude didn’t faze Gilliam, so long as she could do it on her terms. Physically however, getting in front of the camera was challenging. She had only brought with her a twelve-inch cable release, meaning she had to painfully contort her body to get the shots.

When she saw the contact sheet, Gilliam was struck by power of the images, and the paradox they presented: the sense of awkwardness of her body in motion was in sharp contrast to the gracefulness and beauty of the shots. Technically they were all wrong, they were “crap,” she says, but her instructor’s reaction was over-the-top. He pronounced that they were “f***ing brilliant. This is it!’”

Initially, she couldn’t print the photos, feeling she didn’t have enough technical expertise to make prints that would reflect the energy and emotion she saw in the negatives. “I began this work,” Gilliam says, “using myself as the model because it was convenient, but quickly realized that in telling my story, or hinting at it, I was reflecting back and perhaps challenging society's perception of the 'ideal.’” She had begun to discover her voice.

Starting a journey means assessing what baggage you choose to bring with you. When she signed up to take classes with Chuck Kelton, a master printer specializing in gelatin silver prints, at the International Center of Photography in New York City, the first project she produced was called Family Matters.

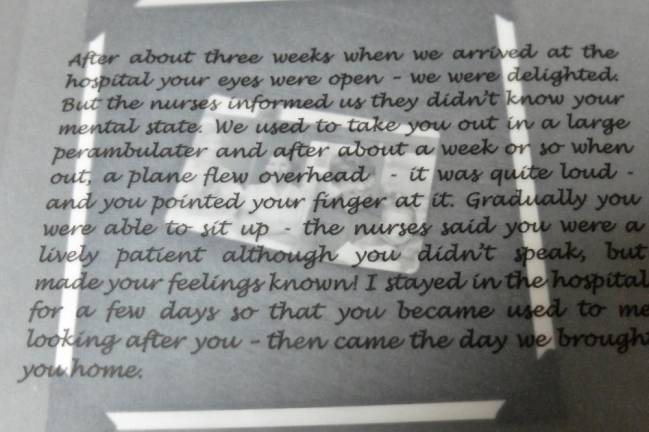

In her studio – the upper floor of a garage in her Warwick backyard – Gilliam pulls out a small black box that opens like a book. Poems she wrote appear on the inside covers, and in between are portraits of the grandparents who raised her and who she refers to as Mum and Dad, and re-workings of old family snapshots overlaid with extracts from letters. “I guess I felt I had to do this. I haven’t shown it to many people because it feels a very deeply personal project,” she says. The letters were written by Gilliam’s family; she asked them to write their recollections of the accident that altered the course of her life. Although she does not include Family Matters in the portfolio of her work, it was a crucial step along her path, addressing the idea of truth and memory in her work.

Finding her voice meant embracing the fear of how others perceive her. As her confidence working with silver gelatin prints grew, she decided to salvage the nude self-portraits she’d shot in Maine. She called the series, I Am My Body. Describing them, she’s written: “Having been stared at frequently throughout my life without invitation, these photographs now challenge and give permission for the viewer to gaze upon my body under my own terms.”

Emboldened, Gilliam shot a new series of raw and graphic self-portraits called This is You, This is Me, that deals specifically with disability. Photographing her body repeatedly brought forth memories of surgeries and falls, and the reactions of strangers towards her. She added bold hand-lettered text to the portraits, literalizing those unpleasant memories, speaking, as she says, of the wider concerns of disability, desirability, body image and difference. One of the pieces was selected for a group show in Chicago called Humans Being II, exploring the disability experience. The piece was titled Spastic, a word that was thrown at Gilliam frequently in England.

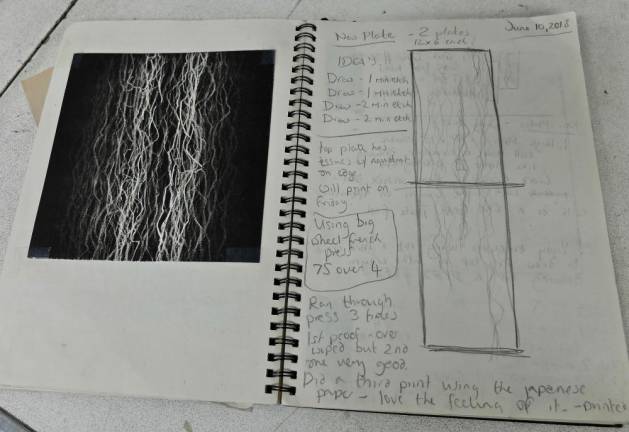

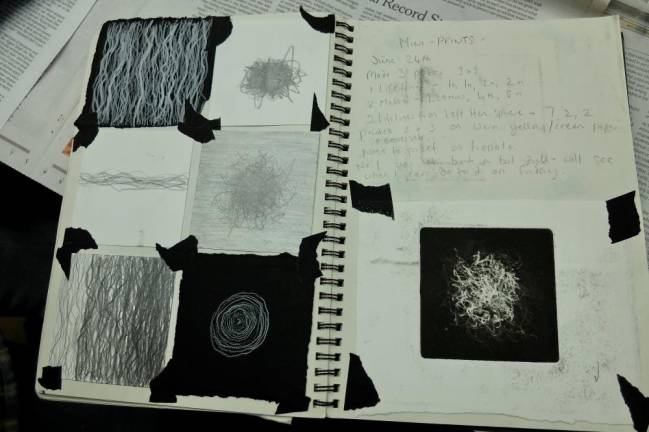

I spent a day shadowing Gilliam at the Manhattan Graphics Center, a long, narrow room with multiple workstations where she is co-president of the board. Printmakers are busy inking metal plates, working on their designs, and sharing technical tips. Gilliam keeps a notebook of drawings, combined with detailed work notes for each project. The lengthy process could take weeks before ending with a print.

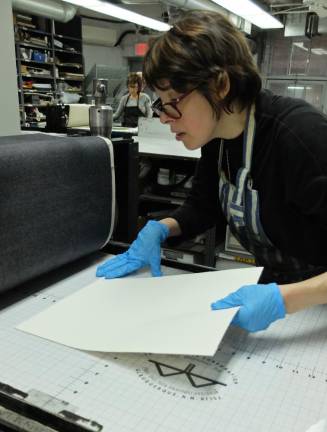

She begins by preparing a copper plate, cutting it to size, beveling and smoothing down the edges. Figuring out how to translate a drawing to an imprint on the plate in reverse is probably the most challenging part, she admits. Only experience will ensure success.

A plate is etched by submerging it in an acid bath, the acid bites into the metal wherever the plate is not coated with a resist. When the finished plate is inked up, these areas will hold the ink and transfer it to the paper when it’s passed through a press. Different resists — hard ground, soft ground, aquatint, litho crayon — all require distinct applications and methods of working.

Often, Gilliam will use a combination of resists on a single piece, combined with hand drawn images and templates. Watching Gilliam work, you sometimes see a gleam in her eye when things don’t go according to plan. Her playful let’s-just-see-what-happens approach is what propels her forward. Although the steps are technical, she can still be spontaneous in her mark making, building layers by etching a plate multiple times, resulting in a range of tones in the finished print.

Etching is physically challenging, requiring strength and dexterity. Along the way, Gilliam has improvised to make her job easier. A wooden block covered with sticky tape serves to hold down the copper plate as she inks it up. She has begun to explore drawing with her non-dominant hand, enjoying the effects of the loss of control.

Gilliam has never shied away from confronting her disability in her art, but mentors over the years have warned her away from getting too personal. “I’ve had conversations with influential people in my art career who say, ‘You shouldn’t be known as a disabled artist.’ Or, ‘People don’t need to know your story.’

“I go backwards and forwards on that, because it’s very relevant to the work that I make. It’s not that I want people to think, ‘Oh my god, she’s disabled.’ That’s not the point. The point is, that’s the perspective I’m coming from and it’s informed my work, and I’m not going to change it.”

See Gilliam’s work at clairegilliam.com.