Keeping the faith... in farming

The radical comeback of the devout farm family

Growing up Muslim in 1980s Rockland County, NY, meant spending a lot of Saturdays in church basements. Nascent community that we were, we didn’t yet have a mosque to call our own. So the kids learned the stories of our holy book, the Qur’an, while the adults socialized and enjoyed their chai, all under the watchful eyes of Jesus and his sheep.

After years of church-basement hopping, my family began attending Friday prayers at a small mosque in Chestnut Ridge, NY. Little did I know that not even half a mile down the street, tucked into a serenely peaceful patch of earth, was a biodynamic farm. My own journey toward the intersection of faith and farming began, quite literally, by walking down the road. (Jesus and his sheep were making a comeback.)

Farming and faith have always been connected. “There was no prophet who was not a shepherd,” said the Holy Prophet Muhammed. And while history generally marks 10,000 BC as the start of agriculture, the Abrahamic faiths – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – might say farming actually goes all the way back to our origins: to Adam and Eve, our first farmers. And while the image might come off as old fashioned, the devout farmer is an enduring icon that appears, in fact, to be enjoying a revival.

Faith in farming means believing in nature, just the way it is, even on the hardest days when the weeds are now taller than you, the squirrels are stealing your entire crop of strawberries, and some mystery insect keeps kyboshing the kale seedlings. As a farmer of faith, you see yourself as a caretaker and steward, rather than a creator and ultimately destroyer, in your own right. You understand your purpose is not so much in making it better, as humans are wont to do, as in observing and learning the way it was meant to be.

I visited three farms for this story, one representing each of the Abrahamic faiths. To listen to these farmers talk about the animals, crops and land under their care is to hear reverence and humility at the wonder of creation. I’ve often noticed people witnessing natural phenomena — sunsets, ocean waves, rare blooms — react with that same sense of awe. And I can’t help but think that if people looked at food in the same way, things might be a little different.

Halal Pastures FarmRock Tavern, NY

Tomatoes are rarely the subject of passionate affection. But for Samer Saleh, who co-owns Halal Pastures Farm with his wife Diane, fervor for his plants is a reflection of his faith.

Samer, like many a farmer, works full-time off the farm, too. When he returns from his job in finance, “I feel like ‘I missed you!’” he says of his plants. “I’m so happy to be back here, because I feel like I’m the only one that can see and care for that plant.”

Growing food all started with a growing family. “I wanted to make sure what my kids are eating is something that I trust,” said Samer. “And in this day and age I don’t trust anything aside from what I do myself, with my own hands.” They have been farming for about six seasons now on their 14-acre property, growing an organic halal family farm that provides their community with organic, pasture-raised meat like Italian sausage and smoked roast beef.

“When I sell something and I say ‘It’s good,’ it must be good,” said Samer. “If you’re seeking the love of Allah, you must be honest, upright, and do things the right way, the way that will satisfy Him. If he’s satisfied, everything else is good.”

Diane and Samer can’t imagine doing what they do without a faith base; it’s part of who they are and how they farm. “When we put the seeds in the ground, we mention the name of Allah [God], first and foremost, with full belief that He’s the one that’s in control of these seeds sprouting and giving us its fruits,” said Samer. “You can put as many seeds in the ground as you want, but without Allah’s baraka [blessing], nothing will come out. I’ve seen it happen with my own eyes.”

As it says in the Qur’an: And have you seen that [seed] which you sow? Is it you who makes it grow, or are We the grower?” Surah 56:63-64

“This year was one of the most amazingly successful years ever for me,” said Samer. “Quite literally every seed that I planted sprouted.”

The reason? Samer points to the gift of seeing, a skill that is always improving, and can always be further improved. “When you continue working on it and you’re dedicated, Allah opens the door and reveals more knowledge to you. You see the minute details that you’ve perhaps missed,” he said. “Now you are perfecting that, and the results become better and better.”

For Samer, success goes well beyond germination rates. “When I feel like I’ve inspired someone to touch and interact with the land, to grow, to cultivate, to eat from the fruits of their own labor? There’s nothing more satisfying than that.”

Yiddish Farm

New Hampton, NY

“I only know maybe two or three other observant Jewish farmers in the United States,” said Yisroel Bass, co-founder and director at Yiddish Farm. “It’s a very radical thing, especially in the Hassidic world, to just go off and live on a farm.” Bass fields my call while headed to pick up his son from school, about a 40-minute “schlep” from his 225-acre farm near Goshen, NY.

He traces his mother’s lineage to Szczuczyn, Poland, where her relatively upper middle-class family ran the town’s department store. A farming future was not what they would have envisioned for their grandson, as agriculture was traditionally looked down upon by the Jewish community.

“Jews that have been in Europe for the last 1,000 years or so have been alienated from the land,” said Bass.

His mother pushed him to become a lawyer. But the journey toward farming started with his faith, and his deep reading of history, specifically of the resettlement plans for millions of European Jews around the time of the Holocaust.

“What can I do today, in the context of land,” Bass thought, that would cultivate his faith and his Eastern European identity in a tangible way.

His “calling” to farming was not the only thing that set Bass apart. His path toward observance started later in life. And in the Hassidic community, he explained, your standing in society can be largely based on how observant you were raised. “The farm gives me a real base, something to stand on,” he said, “that I bring to the wider community. I’m not just taking and taking” in terms of learning and resources. “I have something I can provide as well.” The Yiddish word mashbiah (mash-BEE-ah) means to bestow.

Yiddish Farm has become a place of Yiddish language immersion, using on-farm experiences to give students the opportunity to “live Yiddish” while understanding the role agriculture plays in Jewish tradition. The farm also provides experiential tours and is earning a reputation as the maker of a kosher, organic matzo that is handcrafted locally in the run-up to Passover.

At the core of it all lies intention, said Bass. What am I doing in this moment to fulfill God’s purpose?

“Before I turn on the harvester, I set an intention for the harvest by saying the words, “L’shem Matzos Mitzvah.” This translates roughly: “[this harvest is] for the sake of the matzo mitzvah.”

To hear Bass speak is to understand him as part dreamer, part realist: “To be able to build something from dirt is really cool,” he acknowledged, “but it also gives me the time and the space to grow as a person. Of course, it’s really hard, and things don’t always go as planned,” he said.

Still, there’s no looking back now. “If I would have given up, I would have given up a long time ago. The dream alone is not enough for most people. For me, it is.”

Freedom Hill Farm

Otisville, NY

If you happen to arrive at Freedom Hill Farm at milking time, around 4 p.m. after the cows come in from pasture, you’ll see two very orderly rows of about 48 healthy looking, honey colored Jersey cows contentedly munching their fresh hay. Tails steadily swish side-to-side, pendulum like, sometimes in unison.

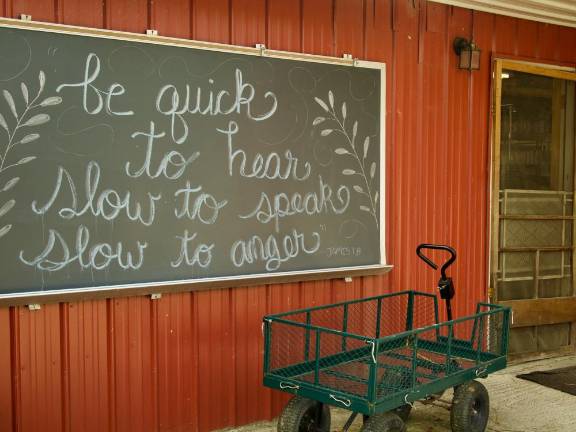

You’ll also begin to notice the Bible quotes and placards, quietly placed on the walls, morsels of inspiration and reflection all at once.

Such is the way the Vreelands run Freedom Hill Farm: “Never in a provoking or controversial way, and never without goodwill,” said Julie Vreeland, who with her husband Rick started the farm in 2003.

I buy raw milk from Freedom Hill, and as I began to visit the farm more often, I became intrigued by their relaxed and gentle approach to Christian ministry. It seemed to infuse and enliven every aspect of their farm, from the swishing of the cows’ tails to the sweet and creamy milk.

But it wasn’t always faith first for Rick and Julie. For over 25 years, Rick managed a 2,000-cow dairy operation in Slate Hill, NY, until they decided it was time for a lifestyle change and sold the farm: “We considered ourselves successful and happy in a totally worldly sense before our life of faith,” said Julie. But it was stressful, too. A vision led the couple to start afresh with a completely different kind and scale of dairy farm, one where they would sell directly to customers. This time, the mission was to create a family farm founded on the principles of faith and doing good for the community.

Dairy farming is not for the faint of heart. Beyond the unrelenting milking schedule, the dairy market is notoriously volatile. Small dairy farms in particular have been packing it in over the last few years. The Vreelands, too, have had their ups and downs. They take daily inspiration from the Bible, updating the chalkboard out front with passages like the following:

The lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to work it and keep it. Genesis 2:15

And when the future looks iffy, as it did last fall, they pray. “We know you bless us. Just bless us so we can pay the bills,” said Rick, recalling that uncertain time. Then the pandemic hit, far-flung supply chains broke down, and the importance of small, local farms was made abundantly clear. So many people started showing up for milk that the Vreelands added 10 cows to their milking herd.

“Ever since we put our hope and trust in our lord Jesus Christ, we have been blessed beyond human measure,” said Julie. “The overflowing, abundant blessings do not compare with our life before faith.” They now sell yogurt, buttermilk and kefir in addition to raw milk, and their son Chris recently returned to the family business, building a farm store on the property and taking on the job of distributing Freedom Hill products to grocery stores from Brooklyn to Schenectady.

While she and Rick are proud of the farm business they’ve built, their connection to the farm goes well beyond the livelihood it provides. “We love taking care of animals of God’s awesome creation,” said Julie. “The Lord blesses many people through this farm, and we feel this is his farm and that we are managing it for him. We strive to follow his path and direction and as we do we feel his peace, joy, contentment.”

Peace. Joy. Contentment. Tastes like fresh milk with the cream on top.

Aysha Venjara is the founder of the Falaha Center for Spiritual Agriculture, whose mission is to grow faith, family and fun through farming.