Backyard revolution

“Don’t take it, Ben!” Suzanne Barish said to her son.

“I’m hungry for a cucumber, Mommy,” Ben, 4, replied. Really, that is music to any mother’s ears. She relented, pushing some leaves aside to reveal another cucumber that he could pick. Just not the one dangling like a jewel in full sight and easy reach of anyone walking along the sidewalk; that one had to stay, for the next person to enjoy.

Ben twisted, pulled, and got to munching while Barish and I talked. This cuke was grown by Barish’s neighbor, and although she was not home, she would approve. Hers is one of about 20 Please Pick gardens that have sprung up since last year, turning Nyack into an “edible village.” Last year, these gardens grew 2,500 pounds of organic food.

“It was just a simple idea,” said Barish, 34. “I didn’t even really think this would be a project.” Barish now finds herself writing grants, tending the garden at the Nyack Center, putting out a harvest calendar, organizing cooking workshops, and countering critics worried about attracting unwanted wildlife. For no pay.

It’s totally worth it.

The idea has the potential to be revolutionary. We lose 40 acres of farmland per hour across the country, while we gain yard space. If we used a fraction of our collective lawn to grow food, what would it do for food security? Our obesity epidemic? Food justice?

When she goes picking, “I like to bring [Ben] so he feels that magic effect of having food cascading down on the sidewalk wherever you go,” said Barish. She and her son were both in bare feet, having popped over from their own yard.

The UPS driver honked as he drove by. Barish waved, then laughed: “I’ve taken on a very suburban existence.” True, she lives in a suburb, but that other definition of “suburban” – contemptibly ordinary – doesn’t apply. It may be quiet, without any fanfare from local authorities, but take a walk around Nyack and you can see that change is happening, even taste it yourself.

“When you live in suburbia, there’s this misconception that of course we have to accept that we’re removed from our food sources,” said Barish, who recently worked as director of communications for the Rockland Farm Alliance. “Maybe we can have this transformation of what it means to be suburban.”

The initial thought was to remove financial barriers to good food, but now families from all tax brackets are taking selfies with veggies around town. Including me. Upon hearing about the Please Pick phenomenon, I Googled the first garden on the list and showed up unannounced. I drove right past it: the address belonged to a house that was boarded up. Driving back more slowly, I saw a double-decker planter on the sidewalk with that “Please pick” sign.

I didn’t plan to pick any food. But then I saw one fingerling eggplant, nestled at the bottom of a healthy plant full of purple flowers. I worked the fruit off, feeling a little sheepish. Probably I should leave it for someone who really needed it, but what a thing, to be invited to grab a piece of produce glinting in the sun. No packaging, no payment. I couldn’t pass it up.

A man walked up with a power drill in hand. “I took an eggplant,” I confessed right away.

“Good,” he said.

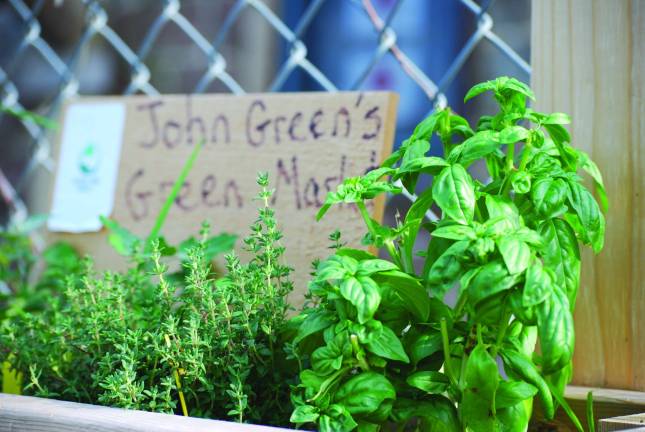

Ken Sharp was his name. He was part of the preservation group that owned the John Green House, an 1870 Dutch sandstone. A handiman, Sharp had built the pine planter, lugged it over in his van and assembled the unwieldy thing on the sidewalk. Why?

“John Green, the guy that built this house, was all about the community,” said Sharp. “We’re always looking for ways to be as well.” The house is being turned into a community space and museum. ‘Til then, the garden is a perfect way to re-forge the community connection.

“Thanks to whoever is watering the John Green patch!” wrote a local actress and mother on Facebook, under a photo of another eggplant. “We visit it every day.”