Inside the hippie cult

Coming of age in the biggest, most audacious commune in American history

By Becca Tucker

The day we met for coffee, Melvyn Stiriss’ life’s work was on the printing press — finally. Stiriss, 75, of Warwick, started writing Voluntary Peasants some 34 years ago, after he’d packed up his young family and driven away from Tennessee and the biggest, most audacious commune in American history, The Farm.

At its peak, The Farm was home to 1,500 self-sustaining, vegan hippies, led by the six-foot-four freethinker that High Times dubbed the Gandhi of the American counterculture, Stephen Gaskin.

Stiriss, a Jewish boy from New Jersey, had been a clean-cut reporter for United Press International before he started dropping acid and moved to San Francisco, where he became an eager follower of Gaskin’s and eventually, a founding member of The Farm. As the only trained journalist of the Farmies, when it split up, “it seemed like my job,” he said, “clearly my duty, to report what happened and what it was like living there.” But it would take time. Decades ago, Stiriss brought an early version by an agent, who told him, “‘it’s not a balanced report.’”

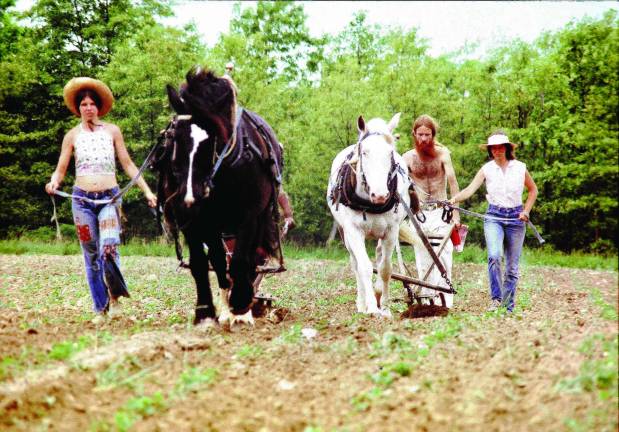

“I realized I was writing it fresh from the experience,” said Stiriss, “like I was the community PR man.” There was so much good stuff to tell, after all, about living life not in competition but in cooperation, about working hard not for money, but because, as Gaskin liked to say, “work is the expression of love on the material plane.” Stiriss came of age surrounded by the “good vibes of community members who were good, honest, hard-working, cool, fun-loving, kind-hearted, generous people.” They’d devoted themselves completely to a bold test of the question: “Can greenhorn, spaced-out city people do what it takes to grow food, build shelter and infrastructure and survive in the country?”

That first winter was hard, but the answer was yes: the longhaired greenhorns managed to set up a working village, with a farm, a soy creamery, a bakery, their own midwives, an international humanitarian arm, a printing press, even their own rock band (a pet project of Gaskin’s, whose expenses, says Stiriss, were part of what brought them down). They did it all while smoking copious amounts of “grass” – but no alcohol, hard drugs, or cigarettes. Or birth control, for that matter.

For a dozen years the farm’s numbers swelled, until 1983, when financial desperation forced them to start charging dues. The Farm in its co-op form still exists today, and Stephen’s wife Ina May Gaskin, a matriarch in the midwifery world, still lives there. But the golden commune days were over, and most Farmies moved on, starting from scratch, since they had given all their property over to the group.

Stiriss and his family moved to hippie-friendly Austin, Texas, along with a couple hundred Farm expats. Like a lot of ex-Farmies, he worked in construction, having picked up building skills by necessity. There was culture shock at first, seeing people with cigarettes hanging from their lips, women with a lot of makeup on. But nowadays, Stiriss himself looks pretty normal. He’s got a short beard and has been vegan for 50 years, but “mainly my freak flag flies within my heart.” About 15 years ago, he moved up to Warwick to be with his current partner, and he admits that they do “un-hippie like things like going on a cruise to Alaska.” One of his kids, Jordan, 43, is a drummer, carpenter and “out and out hippie,” while Sarah, 35, who spent her first nine months on The Farm, is a nurse practitioner and assistant surgeon.

Over the years Stiriss spent thousands of hours interviewing other Farm expats, and gaining the perspective that can only come with time – “getting relativity,” they might have called it on The Farm. “When we started out, I was tripping on LSD and thought that Stephen was the next avatar, the next Christ, whatever you want to call it, a redeemer who would come shake things up and make things better,” he said. Forty years later he’s clear: “Hell yeah! Stephen was indeed a charismatic cult leader, and The Farm was a cult—a benign cult, nevertheless a cult,” he said in his epilogue. “I was so brainwashed that up until just a few years ago, I myself had a ‘Stephen filter’ stuck in my head that asked, “What would Stephen do?”’

Stiriss came to understand that his blind adoration had allowed him to become something of a punching bag. At one point Stephen put him on a “vow of chastity” that lasted over a year, so Stiriss could learn to “be friends” with women. Twice, Stephen kicked him off the farm with the mission, or “yoga,” of earning $1,000 before he could return – and return Stiriss always did. Despite The Farm’s communal ideals, in time a hierarchy developed, Stiriss shows, with the Gaskins too far up on top, and the familiar storyline of communes eventually took its course.

Now that Stiriss could see Gaskin – who died in 2014 – as a man and not a Messiah, he finally had his book, a 424-page memoir. He’d like to make some money on it. (After spending a chunk of his life under, then getting out from under, a vow of poverty, Stiriss says, “Poverty sucks!”)

But he also wants to spread inspiration. “You don’t have to be stuck in a life that you hate,” he said. “You can, on a low budget, get together with family and friends and buy some land and learn how to farm and build your own houses, and it’s actually fun and doable.” He’s printing 500 copies in the first run, available at voluntarypeasants.com, and lining up talks at libraries and colleges.

Did he have any spiritual wisdom to pass on?

“That calls for stroking the old beard,” Stiriss said, caressing his white whiskers.

“Be cool,” he said.

“And work hard.

And love the people in your life.”