Wayne’s World: an emporium of oddities

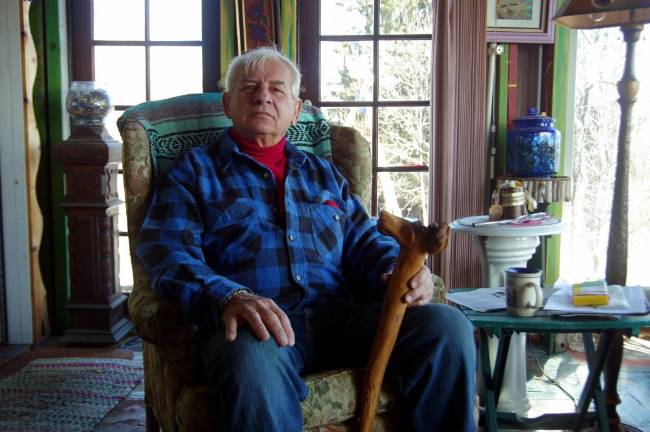

A retired utility lineman molds a dreamscape in the hills

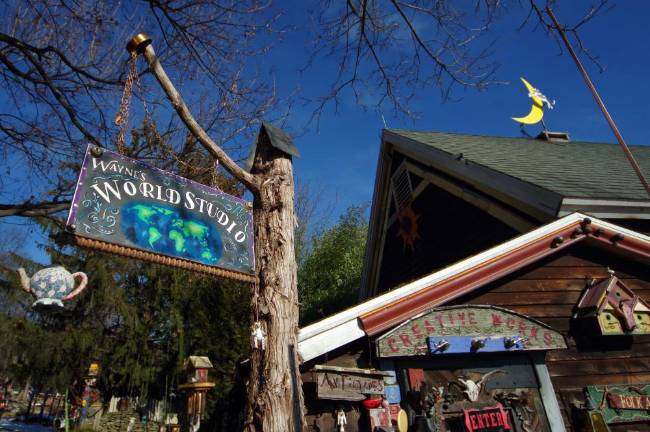

“Outsider artist” is a term thrown around a lot, and if anyone fits the bill it would be Wayne Card. Walking onto his property is like falling down a whimsical rabbit hole that pops out on a back road in Wantage, NJ of all places. There you will find a vista of colors and shapes that, though individual pieces, work in unison to form a dreamscape among the rural hills and farmland.

But what is an outsider artist? The simple definition is an artist who creates outside of the mainstream, and without formal training. Many wear the term as a badge of honor, a guerrilla movement of sorts. Card himself uses the term on the landing page of his website, but personally I have never been a fan of it. The phrase is a form of gatekeeping within the community, a group you’re either part of or an outsider to. That isn’t what art is about. The creation of artwork is about the free form of thought-turned-physical, the tearing down of boundaries and or norms, not the reinforcing of them. An artist is one who creates, and Wayne Card does that in spades.

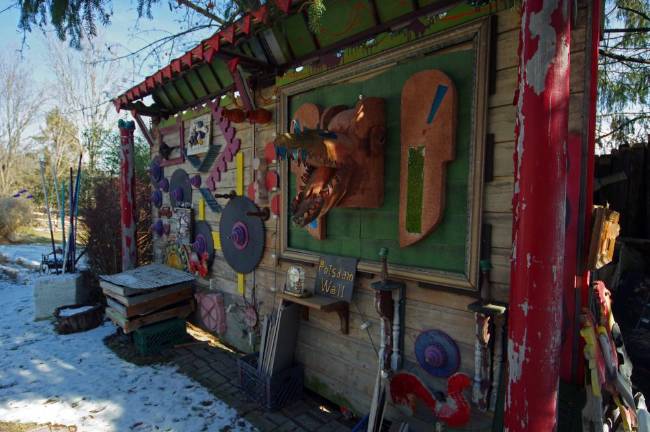

Card was never a career artist, working as a utility lineman for nearly 40 years before retiring. During those decades he was always creating though, typically using his own property and home as his canvas. Most of Card’s work can (very) loosely be described as three-dimensional sculpture, but trying to define it somewhat undermines what it is. These are expressions, all around you as far as you can look: thoughts, memories and emotions. “Some people call this a museum,” he joked, but as I walked with him I quickly understood why. There are lots of found and repurposed objects here, and Card had a story for every last item and creation, like a curator of an emporium of oddities.

Circling back to his home, he guided me into his detached workshop. My eyes immediately went to a large white coffin mounted upon the wall. “So, did you make that coffin?” I inquired, looking at the whitewashed wood facade. “Yea. I’m a cancer survivor, so I was always afraid of recurring cancer. I used to always say, ‘Hun, if anybody’s gonna go first, it’s going to be me.’ So I built my coffin, and Lorraine’s coffin. She passed away, she was able to use her coffin,” he said. “You should have seen hers, it wasn’t like this. I made it like a fine piece of furniture.”

Inside the workshop, a woodstove diligently kicked out heat against the cold of winter. The shop itself was also warm beyond the physical temperature; a creative space that birthed new things into the world. On a shelf stood a small, roughly formed arch, underneath it a signboard with the piece’s name, “Maquette,” and a sketch of the arch with notations about its future proportions: 8 feet high by 38 feet in length. In an opposite corner there was a simple chair and desk with notepad atop it, an inviting corner to sit when musing upon a piece of art, or perhaps life in general. A support column stood just next to it, covered in lineman gear and topped with a hardhat. “That’s all my stuff from work,” he said. “I quit one day and hung it there.” He looked at the gear. “Every so often I may still put these on and climb up a tree.”

“No you won’t, Dad,” interrupted his son, Duane, from the corner of the shop where he had been working.

In the rear of the property, mounted high in a tree, nests a beautiful, vibrant treehouse, accessed by a spiraling two-story staircase.

“I spent the night in there once with my granddaughter. I’ll never do it again,” he chuckled. Omnipresent were reused utility poles, a harking back to Card’s previous life as a lineman. They are incorporated in artworks, utilized as fencing, even found as siding that adorns the facade of his home. Every piece around us had a connection – to a person, a special place or a simple thought which sparked the creation of something grand. “You’re helping me a lot today,” he casually mentioned as we walked the grounds. “How so?,” I asked, curious.

“You’re helping me remember what all this is.”