Not just land access, but sovereignty

An Indigenous reverend’s quest to put down roots

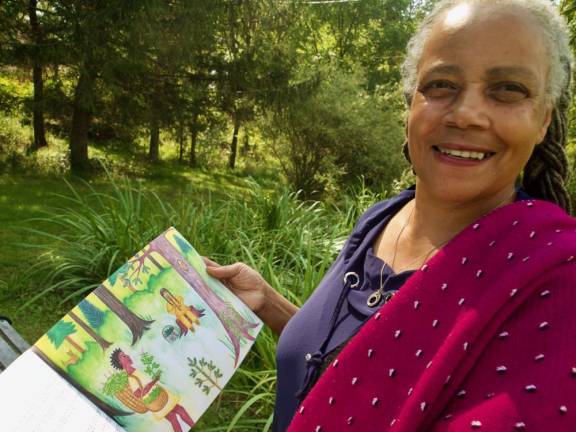

Reverend Dele (del-ee) was in need of sweetener. Anticipating my visit that morning, she realized the time honored tradition of taking tea with a new acquaintance would be incomplete without the palate pleaser.

So she set out for the nearby Finding Home Farms cafe, which specializes in maple syrup products. We ended up meeting right there because it was just too darn cute not to check it out. As it turned out, the concept of Finding Home would be a recurring theme through our conversation.

At 66, the Syracuse-born daughter of an Air Force officer knows a thing or two about living life on the move. Since 2019 though, she’s been living the tiny home life back in New York while co-founding the Indigenous Mothers Community Land Trust. The Trust is made up of four community organizations: Hawk Mountain Earth Center, Soil & Souls, Ramapough Lenape Nation-Turtle clan of New York and New Jersey, and the Northeast Farmers of Color Land Trust. The collective of farmers, market managers, pastors, herbalists, healers and elders is working to create a land-based endeavor that fosters physical, emotional and spiritual healing for communities and individuals. Like many farm enterprises though, the journey of finding land has been, well, enlightening.

“We identified a piece of land up here and we have raised the down payment,” said Dele, “and that will be owned by the Indigenous Mothers Community Land Trust.” Their goal is to first restore the 102-acre tract, which sits just north of Middletown, NY, to its original sacred geometry and eventually create a spiritual sanctuary that includes healing activities, mutual aid gardens, a native/medicinal plant nursery and worker residencies.

But why a land trust? First and foremost, land sovereignty. “I have had land access over a variety of projects over the last nine years and inevitably each landowner did multiple things to prevent my mission from being completed,” recounts Dele. That includes mowing down Dele’s native plantings, applying glyphosate and everything in between.

“We have an unsustainable aesthetic,” she said. “Our concept of beauty is not connected to the earth. We don’t appreciate anything natural. I mean, if you even look at, you know Black women, our hair, it’s a fight to wear your hair natural ‘cause its natural beauty is not appreciated. It has to be messed with.” For Dele, that’s the spiritual part of her work with the land, removing “that fear that says ‘this must be controlled.’” To achieve that, she and her land trust partners need land sovereignty, not just access.

The second part is a cooperative business ethic. “Everything I’m doing is cooperative. As long as you want to work together, you can make it work,” said Dele. “To acquire the land, I also knew I couldn’t do it by myself, and so I needed local people and I needed more than one agency and the fact that the land that we’re looking at is on Lenape territory, it was important to me to have them be a part... I’m bringing up a different Indigenous tradition in terms of how we work the land, but I know that I can’t do that without permission.”

These traditions stem from Dele’s Mi’kmaq ancestry. While she also has Cherokee and Yoruba (West African) roots, she rightly reminds me that “African is also Indigenous. That’s part of the mental separation that we have in our head.” Dele notes that while she has intentionally fused her Christian faith, her Indigenous culture and her work as a minister, it hasn’t been easy.

Dele hails from a family of ministers. Given that Indigenous culture was historically “demonized” by elements of the Christian faith, she’s always been aware of her family’s native roots but until recently had “been undercover for a long time.” Today there is an outright boom in the market for ancestry tracking and genetic testing for lineages, but growing up, she said, “you were not supposed to talk about that.”

While putting together the documentation for the land trust, it came up that in certain jurisdictions, to this day, there are laws on the books that say you can’t put up a teepee in your yard... if you’re Indigenous.

If that sounds like ancient history, in 2018 the Township of Mahwah fought the Ramapough nation over installation of teepees, prayer poles and other religious objects on their own 13.9-acre site near Ramapo College. Only after a federal civil rights lawsuit in 2019 were the millions of dollars of fines against the Ramapough nation dismissed and their right to gather and conduct religious activities on their land acknowledged.

That’s why, when coming to initially see the land, some of the women in the collective commented that they’d have to erect fences so that people couldn’t see what they were doing. Past experiences had taught them that even land sovereignty comes with limits.

Coalition building and a fundraising campaign have given Dele’s vision a foundation upon which to recapture the ways her ancestors connected to the earth: with respect and in community. And she’s gotten the backing of some impressive donors thus far, including the Ralph E. Ogden Foundation and the Kalliopeia Foundation, plus various community donors.

About a decade ago, Dele retired public use of her first name. “Dele is my family’s original name and it means ‘at home,’ she said, “assisting me to feel at home wherever I am.” Here’s to finding that Dele feeling.