The ninth generation

As a town shifts around them, a matriarchal family faces a moment of truth

With the familiarity of a native, I drive past two fast food chains, a shuttered ShopRite and a strip mall that was once an elementary school. I turn into a driveway, where a screen of trees immediately silences the noise of car horns and drive-thru orders behind me.

At the driveway’s end is an incongruously old house, along with other buildings scattered around its outskirts: a two-story mill that once powered a blacksmith forge, a greenhouse attached to a garage, an old chicken coop.

Sitting on the porch is Val Rinaldi – my mom’s best friend, also known as Aunt Val. These 10 acres constitute a fraction of the original several-hundred-acre property that has been in Val’s family for more than 250 years.

“It used to be huge,” said Val. “But in the 1850s, the railroad came. And in the 1950s, the highway came,” opening up Rockland County and paving the way for a population surge that has changed the face of the town. As taxes rose and new construction sprung up, friends and family relocated. So, too, did most of the regulars of the Rinaldi family restaurant – the Waterwheel – leaving the couple and their ancestral home in unease.

“We loved working the restaurant. So many locals came by every day, but it came to the point that that was our only customer pool,” said Joe Rinaldi, Val’s husband and co-owner of the property. “And the longer we stayed in business, the older our customer pool was. It got to the point that our customers were dying on us.” The restaurant closed in 2018, after 20 years in operation.

“It was awful when we had to close,” said Val. “I still don’t think I’m over it. That was me: I was Val from the Waterwheel, and when we closed, I was like ‘who am I?’”

A matriarchal line

Val and Joe’s daughter, Sierra, is the ninth generation to call this place home, a lineage that reaches back to the early 1700s. “It’s kind of weird, but it usually always stayed with the women of the family,” said Val.

Even though she grew up here, Sierra realizes that her house – so familiar – is also remarkable. “I could look through the house for days and still feel like I haven’t touched the surface of this place,” said Sierra.

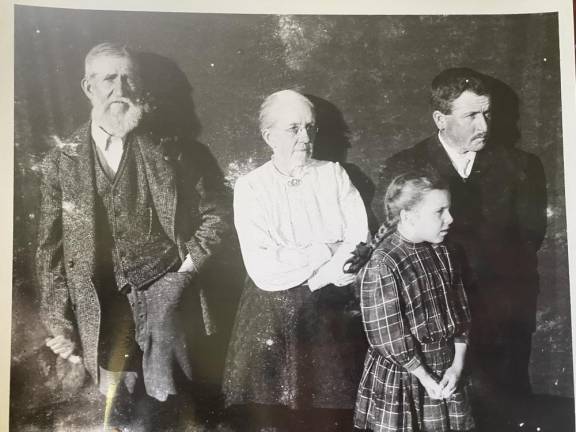

Starting in the late 1800s, sons were rarely born into the family, so for the course of a century the land passed from mother to daughter. Catherine DeBaun took over the property in the late 1800s, then her daughter Mabel Springsteen took the reins in the 1920s. Miriam Osborne, Val’s mother, inherited the home in the 1950s. And Val, one of four children, resides here to this day.

“Which is why the last names always change so often,” said Val, as she and Sierra write out their family tree for me on their kitchen table. “I don’t want to bore anyone with each family member’s life story, you know, but we should definitely talk about John.”

John DeBaun, one-armed blacksmith and mechanical genius

The early history of the property is a little fuzzy; Val isn’t sure who built the house, or exactly when. But one family figure she’s certain of is a distant ancestor named John DeBaun, her great-great-great grandfather. Born in 1827, DeBaun was a jack-of-all-trades: an accomplished blacksmith, businessman, craftsman and author. He created dozens of tools, toys and even musical instruments such as melodeons in his spare time – and operated a small printing business on the side.

Oh, and he only had one functioning arm. In an old photograph, his right hand appears twisted, the result of polio. Far from slowing him down, the disability seems to have heightened his mystique, contributing to the fascination that clings to his legacy.

“We still have his tools and equipment just as he left them in the old mill, his blacksmith forge,” said Joe. “Everything there is made for a left-handed blacksmith.”

Val and Joe recently renovated a room of the old timber frame mill for entertaining guests – it’s called the “bourbon bar,” and used accordingly. Apart from that, the two-story mill remains essentially the same as it was a century and a half ago, with DeBaun’s blacksmith tools hanging where he left them, alongside his coat on a peg. Known as the DeBaun Mill, the timber frame building has its own Wikipedia page and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

DeBaun also owned a tavern down the road where he sold “apple jack whiskey,” made from apple trees on the property. Antique bottles that held the liquor are still stored in an old trunk in the mill. Val’s brothers used to sneak down and drink it, she laughed. “I don’t think there’s any left of it now, though.”

“John was considered a mechanical genius, a writer from the New York Sun came down from the city and wrote an article on him,” said Joe. “It was one of the first human interest articles ever written, I believe.”

The story ran on August 23, 1903, coincidentally, the same day this writer interviewed Joe and Val, albeit 118 years later. “There is little activity in [DeBaun’s] hand, which can feebly grasp an object placed in it,” said the article, of which Val has several copies. “Early he manifested a mechanical turn of mind, and when a boy surprised his parents and playmates by making toys.

“Mr. DeBaun is now 76, straight as an arrow and walks spryly as a young man of twenty,” the reporter effused. “He is ready to converse on almost any subject from the number of barrels of water a minute that runs over the waterwheel in his mill to the action of the nervo-electric forces in hypnotic phenomena.”

A launchpad for generations of entrepreneurial ventures

Over the years, the property served as a launchpad for generations of entrepreneurial ventures, each leaving its own unique imprint on the place. “Each person had their own business, or project, which is really kind of cool,” said Val.

DeBaun looms largest, leaving behind his eponymous mill and enough homemade whiskey for his great-great-great grandkids to enjoy nearly a century later.

Then there was Val’s grandfather, Reggie Osborne, an insurance investigator with Dun & Bradstreet through the 1940s who dipped his toes into an unexpected business in his retirement: floristry. He built several greenhouses on the land, which have been taken down except for one still attached to a garage. “We still grow herbs and vegetables there. We use them for cooking,” said Val.

For a while, Reggie sold his flowers to florists in New York City. Eventually, he opened his own florist business just down the road. From the 1950s through the 1960s, Rockland Florist sold “flowers for all occasions” – as advertised on an old hand-painted sign that still hangs in a hallway of the old house.

Val and Joe joined in the long tradition of family entrepreneurship in the 1990s, constructing a building reminiscent of an old country barn with a red gambrel roof. It operated first as a country market, then they rented it out for a year as a café, until the couple decided to open their own restaurant. When Sierra was two, the Rinaldis opened the Waterwheel, an homage to the mechanism (still poised atop the mill stream) that powered DeBaun’s mill all those generations ago.

‘Are you selling?’

The question that keeps Val up at night is also the one she gets asked the most often: Are you selling?

Val has never lived anywhere else. Her mother, Miriam Harvey, was born and died in the house. “I’m lucky I was able to keep it for as long as I have,” said Val.

We head to the rambling kitchen filled with 19th century dishes and glassware. A Hoosier cabinet sits in the corner holding spices that Val uses on a regular basis, as well as some from decades past. “I should probably look through these,” laughed Val.

“Whenever I need something, like a kitchen bowl or something, I just go downstairs and find one,” Val said. “I’m still finding things I didn’t know we had.”

Val feels the weight of those past generations, now more than ever. “This place is a part of me. Just being the generation that is now responsible is a lot of pressure. I don’t want to be the one who is not able to preserve it,” she said. “So right now we’re just living in it, enjoying it day by day.”