A moveable feast

Imagine this. You’re hoofing it around the city on a hot summer day. Lunchtime creeps up on you. Instead of ducking into a deli for a $10 sandwich, you step aboard a floating food forest and pick a bowl of cherry tomatoes and a handful of basil, pluck a few blueberries from a bush. You walk off the boat without paying a dime.

By the time you read this, this fantasy should be a reality.

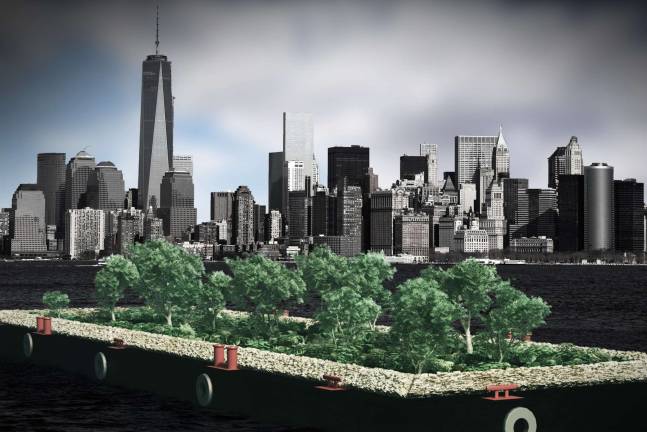

Swale, as the dreamlike project is called, will occupy a 110-by-30-foot barge that will be towed to various points around New York City’s waterfront, and maybe pop over to New Jersey. City dwellers will see the forest growing over months and years, out in the water, from seedlings into a lush forest. Sound impossible? They’ve already bought the barge, with $30,000 raised through Kickstarter.

“I believe it’s not too late to change what the city can supply for us,” said Mary Mattingly, the lead artist, in a promo video. “What if free healthy food was a public service and not an expensive commodity?”

Mattingly has done this sort of thing before. In 2009, she founded Waterpod, which featured an eco-habitat dome atop a barge that was towed around the New York shoreline. WetLand, created in 2014, was a floating public space docked off Philadelphia that cleaned and stored its own water, produced its own electricity and grew its own food. That was where Mattingly met Karla StingerStein, an artist and professor who’s become one of three primary collaborators on Swale.

StingerStein, 42, is a volunteer, like all the others on the project. Many are “cobbling together different gigs” to pay the rent. Why are they working so hard to grow food for random people, free?

“It is for the public one hundred percent,” said StingerStein, who is in charge of sourcing plants and seeds through partnerships with nurseries and farmers. “It’s a collaborative endeavor that we’re all participating in because we believe.”

As a graduate student doing her thesis work in sculpture, StingerStein was in New York City when Hurricane Sandy hit. The storm’s ferocity got her thinking about climate change, and how we had hardened our coastline, cementing over the riparian zone where land and water meet.

“If you look at edge of New York on a Google map, that doesn’t exist at all anymore except for certain areas. It’s concrete; you have a very abrupt shoreline.”

If you’ve spent time thinking about such things, you know it can get you down.

“I was coming from a place of, ‘Oh, we’re trashing the earth, we’re trashing the earth,’” she recalled. She started collecting and making sculpture out of garbage she found in the streets. But it was the act of building the wetland for the WetLand project that tweaked her thinking – just enough to change her whole world. From a place of sadness, she became hopeful.

“Having worked on that project brought me to the other side. I was still able to able to address these concerns, but in a way that was fulfilling and emotionally healthy and constructive. This was very much more, we are solving a problem here. We’re not just looking at the issue and highlighting it, we’re enacting a solution. That was a game changer for me.

“What changed my life was actually seeing wildlife come from it,” she said, incredulous still. “I built it and then all of a sudden there were these creatures that started showing up. We had a blue heron, too. I was like, ‘Whaaat?’”

That project showed her how powerful art can be when it comes out of the gallery and into the melee of everyday life. People had “a lot of questions, a lot of intrigue, a desire to figure out how they might be able to make their lives a little different, too,” she said.

“This is the potential of art.”