DSeekimnorthernmost people on earth

Sixty-seven sled dogs consume a lot of meat. During the winter a single dog at rest can consume 4,500 calories per day, and on an active day, up to an astonishing 10,000 calories. In addition to carrying the usual camp equipment and travel clothing, the sleds were loaded with vast quantities of frozen seal and fish. Even so, it was impossible to carry sufficient food for men and dogs on an excursion they estimated would take many weeks. In order to fill that many stomachs for weeks of hard travel, the six men comprising the Danish Literary Expedition knew they would have to rely on hunting, which added a degree of uncertainty to the expedition. After hauling all day, the dogs became hungry and often dangerously feral.

After nearly two weeks of hard travel, Rasmussen and the Eskimo hunter Elias ventured ahead to break trail and hunt. Melville Bay was one of the greatest polar bear hunting regions in Greenland because the prevailing west winds blew giant icebergs into the bay, and these icebergs sometimes had bears on them. On this occasion, the dogs unerringly led the hunters to two polar bears, which Rasmussen and Elias shot and triumphantly brought back to the others. The great beasts were cut up quickly before the meat froze, and meal-sized quantities were portioned out for the dogs and steaks cut for the explorers.

The dogs were behaving better on a diet of polar bear meat and had stopped eating their harnesses and straps, but the men endured freezing nights in their tents, as they didn’t have either the time or the knowledge to construct snow houses.

When the bear meat ran out, the dogs once again became wild with hunger. The expedition now had barely enough food for a single good daily meal for its members. At this point they encountered the remnants of some abandoned snow-and-stone houses, and what looked like fresh tracks leading north. “The first time one sees a house of this description,” Rasmussen recorded, “one is struck by how little human beings can have and still be content. It is all so primitive, and has such an odour of paganism and magic. A cave like this, skillfully built with gigantic blocks of stone, makes one think of half supernatural beings. You see them, in your fancy, pulling and tearing at raw flesh, you see the blood dripping from their fingers, and you are seized yourself with a strange excitement at the thought of the extraordinary life that awaits you in their company.”

But the huts were empty. In one hut, the men discovered a frozen seal, which they cut up with axes and fed to the ravenous dogs. Exhausted, they collapsed for a rest in the sun after the preliminary exploration. When they awoke, they inspected the sled tracks leading north and noticed that the tracks seemed narrower and the people’s footprints smaller, but the dogs’ paw prints were larger. Things were different here, at the rim of the world. Rasmussen concluded that the tracks were fresh and that perhaps they could overtake the mysterious travelers.

Rasmussen and Jorgen Bronlund, the Greenlandic expedition interpreter, surged ahead, following the tracks as fast as their exhausted dogs could carry them. “All the provisions we could take were a few biscuits and a box of butter,” Rasmussen wrote. “Still, we had our rifles to fall back upon.” Soon the two men came upon even more recent sled tracks and a cairn of stones mounded over a freshly caught seal: people were nearby. They drove on, for another 56 miles. Nearly dropping from exhaustion, they stopped, ate a little butter, and again roused the dogs. After continuing north for a few more hours, with a bitter wind in their faces, they saw unmistakable moving dots on the horizon, dark against the white. “The dogs dropped their tails and pricked up their ears,” Rasmussen recalled. “We murmured the signal again between our teeth, and the snow swirled up beneath their hind legs.”

The two weary travelers surged across the snow plain toward two fur-clad figures, one driving a dogsled and the other riding on it. The strangers had spotted Rasmussen and Bronlund in the distance and now turned around to race toward them. Rasmussen and the approaching man leaped off the runners of their sleds and ran alongside one another, as was the custom, greeting each other warmly while their dogs barked in excitement. The strangers, Maisanguak and his wife, Meqo, stared in astonishment at each other – astonishment that grew when Rasmussen explained who he and his companion were. Maisanguak yelled back to his wife, “White men! White men! White men have come on a visit!”

The expedition had reached the Etah Eskimos, who live farther north than any other people on earth, in a land Rasmussen called “The Kingdown of the North Wind.” They had reached the land of the “New People,” a group cut off from the more southern Greenlanders by a 200-mile ice barrier. Even to Rasmussen, this first encounter with the Polar Inuit was a shock and a revelation. “Never in my life have I felt myself to be in such wild, unaccustomed surroundings, never so far, so very far away from home, as when I stood in the midst of the tribe of noisy Polar Eskimos.” While the children snuck glances from around sleds and huts, dashing away if any of the strangers looked at them, the men passed around a frozen raw walrus heart, each gnawing off a chunk of meat as a symbol of welcome and camaraderie.

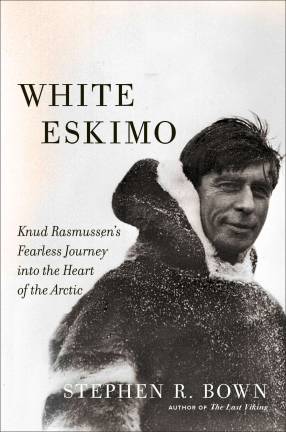

Excerpted from White Eskimo: Knud Rasmussen's Fearless Journey into the Heart of the Arctic by Stephen R. Bown (2015, Da Capo Press, a member of The Perseus Books Group).