The dark, quirky castle on the Hudson

The castle on Bannerman Island is a strong contender for weirdest landmark on the Hudson River. You may have caught a glimpse zipping past Beacon on a Metro North train, or if you’re a boater, maybe you’ve come by chance upon the turret-capped ruins on the shore of the most beautiful island on the river. That’s how I first set foot on Bannerman’s, sliding in on a kayak to poke around. How could I not?

That was a decade ago, and I understand they’ve cracked down on “trespassers” since then. Now you have to buy a ticket to set foot on 6.5-acre Pollepel Island, as it’s called on maps, to get an up-close view of what was once the largest army-navy surplus store in the history of the world.

A committed group of volunteers has been busy since I last visited. The Bannerman Castle Trust has stabilized the crumbling ruins of the old arsenals, which an entrepreneurial merchant named Francis Bannerman built beginning in 1901 to resemble a Scottish castle. They’ve turned the old summer house – a smaller castle – into a museum, begun to landscape the grounds, and now put on cultural events in the warmer months like a five-course dinner, movies and a series of plays.

These endeavors pose no shortage of challenges, considering there’s no running water or electricity on the island, and everything that comes onto it has to be carried up 72 steps – “the Bannerman stairmaster,” as Neil Caplan, executive director of the Bannerman Castle Trust, calls it. Oh, and the actors have to pause every ten minutes or so when the trains go by.

But despite these hard won improvements, Bannerman’s most recent headline grab was as the backdrop of the “kayak murder” of 2015, in which a 37-year-old Latvian woman offed her fiancé by letting him drown, and possibly sinking his kayak, on a cold April day, for which she bizarrely only served two and a half years. His body was found a month later near West Point. As legend has it, he was far from the first to meet his watery end here, off the island that sailors and Native Americans thought to be haunted by hostile spirits.

This time, my second visit, I made land on the island’s north shore, stepping onto a dock equipped with Porto Pottys and no trespassing signs, along with a ferry full of journalists and actors. The actors were scouting a better location for the stage this year, maybe further from the shoreline and the sound of the trains. The reporters were happy to have a reason to be out of the office on the first really spring-like day of the year. We tromped past blazing forsythia after our tour guide, Wes Gottlock. Gottlock and his wife are history buffs who’ve written two books about the island. He claims to keep an eye out for unwelcome visitors from the window of his condominium in Plum Point.

We march up the Bannerman stairmaster to the looming castle façade, which still bears the imprint of the giant words “Bannerman’s Island Arsenal.” He clearly meant his castle to be not only a place to store his ever-growing supply of ammo, but also a billboard to end all billboards. He was savvy, a true American up-from-the-bootstraps capitalist. When Bannerman went to California to bid on government cartridge boxes, for instance, he avoided heavy rail-freight charges by chartering an entire clipper ship to take his purchases back to New York via Cape Horn. His life’s biggest purchase included 30 million rounds of ammunition after the Spanish-American War. At the height of the business, you could buy a cannon and shot, a machine that could cast over a hundred thousand bullets a day, a Congo blow-gun arrow or an original Union army uniform still in its case – for cash, no questions asked.

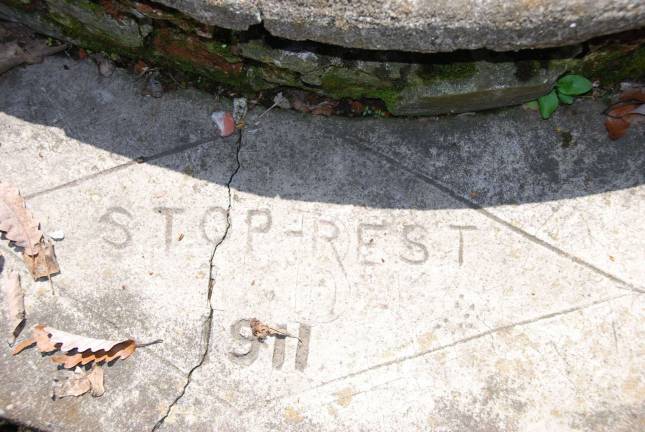

Francis Bannerman was no architect, but he had a thing for Scottish castles and designed the buildings himself, back of napkin style. The man had some “curious architectural quirks,” said Gottlock. For instance, the castle contains no right angles, and its walls were fortified with random military surplus like bedframes. Clues to Bannerman’s multifaceted persona are still visible, like the stone bench with the word “stop-rest” engraved above the year 1911. A handful of cement mounds around the island bear testimony to Bannerman’s love of flags, though he had to take the poles down when he discovered they were a lightning hazard.

Bannerman bought Pollepel Island from Mary Taft, a teetotaler who was happy enough to sell it, provided that Bannerman sign a document saying that the island wouldn’t be used for illegal activities. She had bought it only because she didn’t like the prostitution and bootlegging that had been going on there. Moving Bannerman’s huge store of explosive ammunition out of the city and onto an island made good sense, a fact that was reinforced by the powder house explosion in 1928 that sent chunks of a building across the river and onto the train tracks.

In its heyday, the island hosted a booming business and something of a white-glove social scene in the summers. But by the time the military surplus business had faded in the sixties, the island didn’t make much sense anymore as an investment. The Bannerman family couldn’t find a buyer. What with the hazardous materials, the ruins, and the no-electricity-or-water thing, it ended up in the hands of New York State. Now it’s a public park, but one that you can only visit with ticket in hand.

I get why the island is off-limits: a third of the castle’s front wall collapsed in 2009, and for all the efforts at preservation it’s only a matter of time until more follows it back to the river, whence the brick originally came. But what a shame that you now risk getting arrested for trying to take a boat out to have a picnic on the craggy shores of what’s arguably New York State’s most beautiful park. On the day of the tour, you could see miles downriver to the sparkling bend where West Point rises from the cliff face, another monument to our military heritage.

In days of old the island was as much public property as the river itself. As Charles Bannerman, a son of Francis’, wrote in 1962: “The scenery of the River makes it one of the most beautiful spots in the East for cruising and boating. On stormy days when the River is too rough for sailing, it is exciting fun to sail small boats in the harbor… From the earliest times the Island was used by River fishermen principally during the shad runs in the Spring.”

Is there no way to fence off the ruins? Or will we have to wait for these castles to crumble completely before we can come and go freely to the island again, taking our own chances with what Charles Bannerman calls “the goblins of the Highlands”?