7 habits of effective fracktivists

Part 1: When David meets Goliath

‘No one is going to step in and save us. We have to fight for it.’

Can a handful of concerned citizens take on big energy and win? Sometimes it’s hard to see how.

Here at home, Orange County residents have galvanized against the construction of the tenth largest fracked-gas fired power plant in the United States, which is going up as you read this on Route 6 in Waywayanda, just a few miles from Middletown and the SUNY Orange campus. They’re protesting every Saturday on-site. They’ve held fundraisers and two packed educational forums. Actor James Cromwell and other activists chained bike locks to their necks, blocking the construction site, and got hauled off by the cops. Celebrity environmentalists have joined the fray, like filmmaker Josh Fox and former Ohio Congressman Dennis Kucinich. Despite it all, CPV’s men and machinery persist in erecting a plant that a growing band of locals see as a huge environmental hazard.

Then came the breaking news. The feds had launched an investigation of close Cuomo aide, Joe Percoco, for accepting large sums from CPV. Would it be a game changer? The probe made headlines in all the major news outlets. “Ex-aide to Governor Cuomo pocketed big money from entities with business before state,” trumpeted the Daily News. Has construction paused while they sort out whether the contract to build this plant was won by bribe? Take a guess.

The plant, scheduled to open in 2018, is cited by residents as a threat not only to the county’s agricultural community, agritourism industry, property values, and water supply, but as a significant and unnecessary health hazard for people and livestock. Prime features of concern are two 275-foot towers that will spew pollutants and 2.1 million tons of greenhouse gases over a 30-mile radius, a storage tank that will house 15,000 gallons of potentially volatile ammonia, and a compressor station and pipeline prone to leakages of methane gas.

“Our public officials are opening the door to out-of-state companies that want to use our own resources — our land, our air, our water — at the expense of our health and safety,” said Pramilla Malick, founder of Protect Orange County, which is fighting to shut down the power plant.

To offset pollution regulations, CPV has purchased pollution credits, a market-traded commodity, to make up for any toxic emissions that exceed the already antiquated government regulations. Pollution credits are designed to keep global emissions at a set level, but result in some areas being sacrificed to over-exposure.

“You cannot trade poisons and trade victims and call it an environmental victory,” said Malick.

“We didn’t need more power,” said Sustainable Warwick’s William Makofske, a former Professor of Physics at Ramapo College, summarizing the results of a 2014 study by the New York Independent System Operator study on the need for more energy projects. New York actually may be putting consumers at financial risk due to an overreliance on natural gas, the Union of Concerned Scientists found.

All good arguments, but will they have any more effect than throwing pebbles at an oncoming tank?

In May 2016, FERC approved the Millenium Pipeline connection to CPV and the company plans to use eminent domain to set it through private lands. Three affected homeowners are gearing up for lawsuits to protect their homes.

When the odds appear insurmountable, activists remind themselves of the Shoreham-Wading River Nuclear Plant on Long Island. The plant was fully built, but never operated. It was shut down in the 1980s due to public outcry and help from then Governor Mario Cuomo. They remind themselves of the Keystone XL Pipeline, which President Obama rejected in 2015. Of the Constitution Pipeline, which Governor Andrew Cuomo killed when he denied its water permits. Cuomo could stop CPV with a stroke of his pen if he denied Millenium Pipeline the water permit it needs to transport fracked gas to the plant.

“We are bird-dogging Cuomo,” said Malick, who personally delivered 10,000 pages of documents to Cuomo’s home in Mt. Kisco and kept a vigil on his doorstep. “He can stop this plant tomorrow if he decides to. But no one is going to just step in and save us. If we want a democracy, we have to fight for it.”

Part 2: Here’s how David lines up his best shot

We asked successful fractivists to share their secrets

Connect up

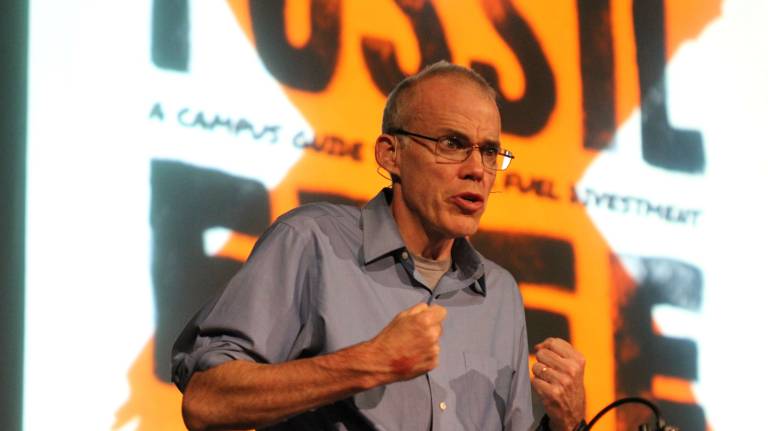

“Organizing is the same the world over. Just talk to lots and lots of people and convince them that they actually have a chance to win. And then, if there are lots and lots of them, they do win!” said Bill McKibben, one of the most successful organizers the international environmental movement has ever produced. “We started with myself and seven undergraduates at Middlebury College. It was before Facebook, but we used every tool imaginable, like Flickr. We were described as the first large-scale effort in ‘open-source organizing.’ It was like a potluck supper. Everyone around the world brought their own creativity to bear and we just collated it.”

Today, his website 350.org — the first international, grassroots climate change movement — has organized 20,000 rallies around the globe, led the successful fight to stop the Keystone Pipeline, and initiated the growing movement to divest from fossil fuel.

“For me, the most important habit in recent years has been to try to push others forward into the light. I don’t think we need great leaders in this movement—we don’t have a Dr. King, but we do have thousands of people leading thousands of local fights across the planet. Often, the most useful things I do is simply to write and tweet about their effort to help others connect up.”

Never give in

Pramilla Malick didn’t set out to be an organizer.

“A few years ago, I got a letter saying that a compressor station would be built near my home. Because I live in a zoned agricultural district, I assumed there was an error.” Then construction began. Malick posted flyers and distributed them in her community. She founded Protect Orange County, led an on-going weekly protest, spoke and networked widely, commissioned studies, and inspired many others to help stop the plant.

“It is time for the public, the agencies, and the governor to step up and stop this. Even if it does get built, we can still stop it. The question is, do we have the will? Do we want to be an industrial wasteland, or a place where families and agriculture can thrive?

“Health and safety, air and water are not partisan issues. When people speak collectively, public officials respond. That’s the one card we have left. Call or e-mail your local, state, and federal representatives every day and ask why they are not stopping the plant. Don’t take ‘No’ for an answer!”

Be positive, be patient

“I have a very un-cynical perspective about the possibility of change,” said Michael Sussman, the lawyer for opponents of the CPV plant, who worked as a campaign advisor to President Carter.

“There are several keys to prevailing. One is not to waste energy focusing on personalities. Focus on binding issues and address them simultaneously, not sequentially. When I was organizing in Yonkers people had lots of different needs, but the fundamental problem was racism. Finding the fundamental commonality leads to the position that ‘We all have to support each other.’”

An advocate for both social and climate change, Sussman has created Empowerment Centers in Port Jervis, Liberty, and Ellenville to help communities in need address issues like homelessness, education deficits, and the arts.

“I have learned that institutions are hollow. Change is far more possible than people realize, but many get paralyzed. You gain credibility with people by being on the front lines with them and responding to the needs they have. You need to have good information to bring to the table, but you also have to be patient. People come to conclusions over a long period of time.”

Be strategic

How can citizen groups triumph against the powers that be? “You develop a strategy based on long- and short-term goals. You look for who can give you the win. Then, you focus on that person.”

As a founder of the global environmental group Food and Water Watch, Wenonah Hauter led the successful campaign to ban fracking in New York State. “We brought the coalitions in New York together and kept our eye and our tactics focused on the decision-maker, and that was Governor Cuomo. But we cannot stop there. Fracking is now part of the presidential race conversation. We have to keep building, state by state,” said Hauter, author of the exposé Frackopoly.

“Our democracy is only as good as the energy people put into it. We don’t just lobby Congress, we work with the grassroots and help to get good local people elected. It’s a long process. People are encouraged to watch T.V. and consume, rather than get involved in their communities. But if we want to prevent climate chaos, it’s time to fight for what we really want.”

Follow the science

“I got involved [in fracktivism] because I’m a biologist,” said Sandra Steingraber, ecologist, author and cancer survivor. “I had studied the horror of fracking.” After traveling to 26 states to see fracking sites, Steingraber “came back determined to not just study fracking but to stop it.” Speaking at medical universities about the dangers of natural gas, writing books that combine ecology with humanity, donating $100,000 to anti-fracking campaigns are some of the ways that Steingraber fights against fossil fuels. Her civil disobedience landed her in jail, locked away from her two children for 10 days, when she blocked a chemical truck in 2014 in defense of Seneca Lake, NY.

“We are fighting for water. We are fighting for life itself. We will not give up. Not in jail. Not in the rain. Not in the snow. You can’t freeze us out, starve us out, or arrest us out,” Steingraber wrote on her way to jail.

Although Steingraber doesn’t believe that direct action is always the best solution, it becomes the only option when the data can’t speak. “If companies don’t share the math showing how much shale is in the wall of a cavern, then science can’t do its job,” she said.

Steingraber’s motivation is her children. “My son, who was just a little boy when the gas industry was announcing upstate New York would be an area for fracking, was my main reason for getting involved.” Based on the science, it was clear to Steingraber that the fossil fuel industry is unsafe. She lives in fear that the industry will “steal children’s future by polluting the air, ruining roads, and worsening climate change.”

Look at the big picture

Environmental projects can get you wrapped up in the details. Fracktivist Emmalyn Garrett, 31, reminds us to use specific issues as a bridge to the larger questions.

Garrett has been working on stopping the Jordan Cove pipeline, which would run through the rural southern Oregon neighborhood where she grew up. “Being in a small and poor and rural place, it is not surprising that this is where they plan to put the pipeline,” she said. As a member of the activist group Earth First!, which fights big industry through protests and monkeywrenching, Garrett has radicalized Oregon locals to challenge what they see as an ecologically dangerous pipeline through direct action.

The fight has been long and tiresome. “People have fought this for 12 years, which makes people tired,” she said. Her cure for activist fatigue is to contextualize the issue globally. The fight is not about stopping one pipeline, but about building power. They might not “win” next month, or even this lifetime.

“Understand that combating the fossil fuel industry is a long term process, and confronting climate change issues is a multi-generational struggle.”

Find your leverage

This spring, energy giant Kinder Morgan withdrew its application for a 420-mile Northeast Energy Direct pipeline. Why?

Emily Kirkland, a recent Brown University graduate and the director of organizing for 350 Massachusetts for a Better Future, explains how the $3 billion project ground to a halt.

When 350 Mass heard about the Kinder Morgan pipeline in 2013, immediately the organization began collaborating with local groups of ordinary citizens. It was “the local folks who identified the problem and found their leverage,” said Kirkland. That critical detail was Kinder Morgan’s proposal to add an additional tax to its electric bill that the governor, then Charlie Baker, had the power to veto — which he ultimately did.

“It seems deeply unfair to me that we would be asked to subsidize new gas pipelines,” Kirkland told the Boston Globe in July. “Alternatives like wind and solar ... are the right thing on climate, and we should be investing in those.”

While Kirkland and 350 Mass worked to amplify the efforts of the local activists, her organization just “followed the lead of the local folks.” After all, as Kirkland recalled, “the folks on the ground made a hell of a fuss.”