Produce to the people

Attacking the twin beasts of food waste and hunger

By Becca Tucker

There comes a time in the summer, as many a home gardener knows, when you just can’t look at another zucchini. On a farm, that zucchini tsunami occurs on another scale entirely.

“These were picked Friday, brought to market Saturday,” said Jeff Bialis, of J&A Farm in the black dirt of Goshen, NY. Now it was Thursday, and hundreds of pounds of beautiful summer squash — green, yellow, striped — needed to go, to make room for the beans being picked at that moment.

“We do 350 different varieties of vegetables, and there’s always something coming in abundance,” said Bialis. “We can’t always sell it all at our markets.”

J&A Farm is one of the twenty-odd farms this season that are working with Stiles Najac, the force behind Cornell Cooperative Extension’s Gleaning Project. Before they hooked up with Cornell, Bialis either composted surplus veggies or fed them to his chickens (and anything that’s not in good shape still gets enjoyed by the laying flock).

For a small-scale farm like his, “Doing wholesale is not always worth it,” he said. “The idea of being able to give it to people that really need it, who can’t get to markets to get it or can’t afford it? It’s really satisfying.”

We were standing around at his 14-acre vegetable farm, waiting for Najac and her refrigerated truck, the Gleanmobile.

“Have you met Stiles?” Bialis asked.

Not yet.

“She’s always late,” he said. “And she’s giant. Like, six-two.”

Six-two indeed (I asked, later). And it’s a good thing; when Najac eventually pulled in, all smiles, it was immediately clear that a tiny person would not be a good choice for this job. Her truck was already three-quarters full of things that she’d moved into it that day, like squash, cucumbers and fava beans from a farm in Middletown, and four entire pallets of spinach from a packaging facility in Newburgh.

“This stuff is in better shape than you could get at the grocery store,” she said. “I got some beautiful red leaf lettuce that just makes me weep it was so gorgeous.”

She put on her work gloves, hiked up her jeans and jumped up on the loading dock, where she got busy re-packing Bialis’ surplus— herbs, radishes, garlic scapes, lettuces and of course zucchini — into her own waxed cardboard boxes.

BYOB: bringing her own insulated boxes is crucial to making this system work, since they cost $2 and change a pop, said Najac. She just dropped a thousand bucks on boxes. If she didn’t bring her own, farmers couldn’t afford to donate. I looked to Bialis, who nodded his agreement.

“Want to see a trick?” Bialis asked Najac. Instead of carefully (read: slowly) dumping each box of zucchini, as she was doing, he set one of his boxes inside one of hers, opened it from the bottom and lifted his box off. Voila, a saver of precious seconds. Then Bialis headed off to the packing room to rinse freshly harvested radicchio, while Najac filled her truck.

“Farmers don’t have the time,” Najac said. “The reason the program is a success is a paid employee is putting in effort. We’re being paid to not forget, to focus on it.”

In its decade of existence, the Cornell Gleaning Project has grown from moving 70,000 pounds to a whopping 270,000 pounds of food a year. And it does so on a relative shoestring, moving food at less than a quarter of what it costs the food bank to do it. This year, a $170,000 grant from the Hudson Valley-based Dyson Foundation covers the three salaries of Najac and her seasonal assistants, the truck, insurance, boxes and fuel.

But no matter how much food the Gleanmobile diverts from the compost, it’s never enough. “Every year I get more donated,” said Najac. “And every year I fail to satisfy the needs” of the people who are, increasingly, depending on her.

Fast forward to the next morning. Najac had let them know I’d be coming, but at her first stop — St. Francis of Assisi in Newburgh — my presence was awkward. Understandably so. A white woman with a camera and notebook, barging in on a sensitive early-morning scene. None of the people milling around the front steps wanted to talk to me, in English or my faltering Spanish, about the truck that brought the vegetables. Even the volunteers were loath to be quoted.

When the Gleanmobile pulled up (a little late, of course), the scene got livelier. Jamar Brown, 29, jumped up in the back of the truck to help haul broccoli, squash, cucumbers, and 80 pounds of spinach. Najac, wearing a Cornell t-shirt and shades, handed boxes of spinach out of the truck three, four, even five at a time, to a few willing food bank patrons who ferried them inside.

Inside the lofty food pantry room, ceiling fans rotated slowly. Folding tables were lined with non-perishables like cereal, infant formula and baby food pouches, pasta, juice, cans, ramen, as well as boxes of bananas and bags of rolls. Next to the mountains of boxes, the fresh offerings looked slight: one plastic bin of tired looking bagged spinach, one of cellophane-wrapped button mushrooms, and another bin of heads of celery. This would likely be the extent of the vegetables if not for the boxes that were just now walking in the door. After all, there was no refrigerator.

The Gleanmobile’s magic is that it is the fridge, the giant moving fridge that arrives just as the people do, so that cold storage is not the food pantry’s problem.

“As soon as I started storing in the truck,” said Najac, “the amount they requested tripled.”

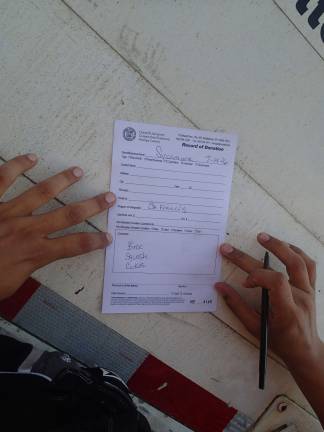

Najac was disappointed with the numbers here. Usually, she said, the line winds around the block. Using the truck as a writing surface, she jotted out a donation receipt — which can later earn farms a tax deduction — and was off to the next stop. The clock was ticking, on this 88-degree day, to get this produce to the people who would eat it.

The low turnout was because a monthly food pantry across town was also open on this Friday. So I tagged along, tailing the Gleanmobile through Newburgh to St. Mary’s Church on South Street.

Here, the hustle and bustle felt almost festive. Marietta Allen, the director of outreach at St. Mary’s, came to the doorway of the church gym. “I want a thousand pounds!” Allen hollered to Najac, who was standing in the back of her idling truck. I thought she was kidding. She was not.

This pantry, located in the poorest part of Newburgh, will distribute 15 tons of food today to 1,300 families today. “Instead of waiting on line every week, they come once here, we load ‘em up,” said Allen. “They’re walking out of here with close to $200 of food and they’re good for a month.”

Allen sat me down at her folding table and started talking, keeping a sharp eye on the scene. “They’re taking more than one!” she shouted to the volunteer handing out the ten-pound packages of chicken. “You gotta watch.”

The 400 pounds of cucumbers, 200 pounds of squash, and 400 pounds of spinach that arrived via Gleanmobile are a “tremendous help,” said Allen. “We get food from Latham,” the Regional Food Bank of Northeastern New York, “but it’s hit or miss. With Stiles it’s much closer, much fresher, and they work with us. They get here early in the morning because we don’t have room to store it.”

And that box of garlic scapes? Najac put out a clump and told the volunteer manning the veggies: a scape is to garlic what a scallion is to an onion. The volunteer repeated the line as the patrons filed through. A few women nodded and took a handful, and Najac raised a hand, victorious.

Then she was off again.