A different kind of midlife crisis

Some people retire in their 60s. This busy pair of New York City professionals took on the project of their lives, converting a run-down farm upstate into a sanctuary to rescue animals from slaughter. First stop: a live meat market in the Bronx.

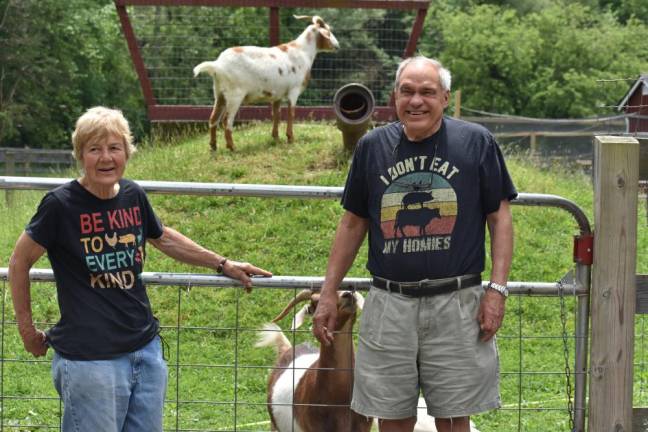

When my wife Ellen and I entered our 60s, we began a new project. We renovated a run-down farm in upstate New York and turned it into Safe Haven Farm Sanctuary. The sanctuary provides a lifelong home to farm animals rescued from slaughter and abuse. We have been taking in animals for the past 16 years and currently have 170 animals, including goats, sheep, chickens, turkeys, pigs, donkeys, cows and horses to whom I’d like to introduce you.

First, though, I should describe how we began the farm sanctuary.

Ellen and I were busy with our professional lives. Ellen was the director of the pediatric emergency room at Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx. I was a psychology professor at the City College of New York. Our occupations demanded a great deal of time. We weren’t looking to add a major new activity.

But another force was at work within us. Over the years, we increasingly found our hearts going out to animals; we worried about their plight.

Ellen was reading a great deal about factory farms, which provide most of the meat sold in the United States. Factory farms don’t fit the popular image of a farm. They do not have pastures in which animals happily graze, nor do they have barns in which the animals eat hay and bed down for the night. Instead, factory farms consist of huge concrete buildings in which chickens, pigs and other animals are crammed into spaces so small they can barely move. Most of the animals are forced to stand on wire or concrete. They will never experience sunlight, breezes, soil or grass.

Ellen wanted to do something to help these animals and read about the impressive work of the Farm Sanctuary in Watkins Glenn, NY. This sanctuary, like the others that have followed in its footsteps, cares for animals who somehow escape factory farms. For example, a cow, chicken or pig might occasionally escape a slaughterhouse. Or some animals might get free of their crates when a transport truck gets into an accident. Passersby see the animals wandering loose, want to find them a safe home, and call the sanctuary to see if it can take them.

Farm sanctuaries can only save a tiny fraction of the 10 billion land animals that are slaughtered for meat each year in the United States. But the sanctuaries can also host visitors and publish articles about their animals, making the public more familiar with the animals that are being killed. People might then give more thought to their food choices.

Ellen was initially more enthusiastic about creating a farm sanctuary than I was. I agreed that farm sanctuaries are important, but my preferred way of working for a cause was political action. I frequently spoke at public hearings and participated in protest rallies. I had even engaged in civil disobedience in an effort to protect trees and black bears. [Dirt interviewed Crain in 2019 at the Sussex County Jail, where the then-75-year-old was locked up for 16 days for a deliberate act of civil disobedience protesting the New Jersey bear hunt]. I wondered if I would have the patience to care for numerous farm animals.

But the more I thought about starting a farm sanctuary, the more I liked the idea. I would get a chance to learn about nonhuman animals, who have provided my profession – psychology – with insights into human behavior. For example, psychologists have learned about human toddlers’ attachment to parents by examining attachment in other species. In recent decades, animal research has lost some of its popularity in psychology, but it remains important. Perhaps, I thought, a firsthand knowledge of animals could contribute to my teaching and academic writing. This possibility began to excite me, and I agreed with Ellen’s wish to establish a farm sanctuary.

We purchased the farm in 2006 and looked for a contractor to renovate the buildings on the property. These structures – a small house, cottage and barn – were in such dilapidated condition that the first three contractors told us to tear them all down and start over. But among the shambles was some fine wood craftsmanship, so we kept searching until we found a contractor who wanted to restore them.

Construction took two years. Once it was completed, we named the farm Safe Haven Farm Sanctuary and got ready to open it to animals. Because Ellen and I couldn’t live full-time at the farm yet, we hired a caretaker, a young woman named Stacy. Stacy, who had been living in Connecticut, drove to the farm with her beautiful mare and a chicken who had been abandoned in a pasture with a broken leg. The chicken, a hen, was our first rescued animal.

The next group of animals came from a live meat market in the Bronx. My experience at the market was one of the worst of my life.

The live meat market

Live meat markets allow customers to walk in and select the kind and size of the animal they want slaughtered and butchered. This is done on the premises, so customers can be certain their meat is fresh. In most of these markets, the majority of the animals are chickens, which are usually crammed on top of one another. Many of the markets also sell ducks, guinea hens, rabbits, goats and sheep.

Ellen and I had driven by a market in the Bronx several times, and we had often seen a large sheep standing near the front door. Sometimes we saw one of the goats. Occasionally, people purchase an animal from a live meat market to save their life. We later learned that most farm sanctuaries oppose this; the purchases, they point out, support the markets’ business. We came to see their point. But at the time, the sight of the animals made us want to do something. So when our farm sanctuary was ready to house animals in February of 2008 we decided to save a few from this market. In particular, I had my mind of the sheep by the door.

Ellen and I rented a truck, put hay in the back, and drove to the meat market. It was a chilly Sunday morning. When we arrived, we were joined by our farm’s first caretaker, Stacy, and her friend Tom. We walked into the store, talked to the manager, and purchased the sheep we had seen by the door. We also bought a second sheep – a recent arrival who was the only other sheep on the premises. The two sheep frantically tried to escape being grabbed by the workers, but they were caught within two or three minutes.

When I turned my attention to the goats, I started feeling upset – even a little sick inside. How could we decide whom to save? Saving two meant determining that the others would die. But the manager didn’t ask us to choose. He just told his workers to capture two goats. As soon as the workers stepped into the goats’ room, all of them, like the sheep, ran for their lives. The goats were quicker and more difficult to catch. It took the workers about fifteen minutes to grab two of them. So we didn’t make any selection; our two goats were simply the two the workers could capture.

Once a worker caught a sheep or goat, he held the animal by the feet and flung the animal upside down. He then dragged the sheep or goat about 30 feet across the cement floor. When he reached the large scale for weighing, he flung the animal onto it. If the animal was very heavy, another worked helped throw the animal onto the device. We pleaded with the workers to be gentler, but they ignored us. We paid the manager, put makeshift leashes on the animals, and with some pushing from behind, guided them into the back of the track. They were all trembling in fear.

On the trip back to the farm, Ellen, Stacy and Tom drove a car, and I drove the truck with the goats and sheep. The trip would ordinarily take an hour and a half, but I lost contact with the car and took a wrong turn. For another half hour, I couldn’t figure out how to get back on the correct highway. I soon began to worry about the animals’ health. The truck doors are all closed, I thought. If this trip takes longer than I planned, will the animals get enough air?

I knew nothing about such transports. Should I pull the truck over and open its back door to give the animals some air? Or might they jump out and run onto the highway? Finally, I did stop and peek in. They were huddled tightly together but breathing okay.

After three hours of driving, I steered the truck up to the barn. Ellen, Stacy and Tom were waiting. I sensed that they were irritated by my delay, but they didn’t say much because we all had to focus on getting the animals out of the truck and into the barn. All the sheep and goats were scared to death. Pointing to the smaller goat, Tom said, “This one is trembling something awful!” Tom tried to calm her by stroking her back, but to no avail. He told her, “You’re scared now, but you don’t know how lucky you are.” That night, Stacey named the animals and called this small goat Mattie.

We kept the sheep and goats in a quarantine stall for four weeks, while we had them tested and treated for parasites and other illnesses. During this period, Ellen and I had to work in the city, but we traveled to the farm several days a week. I spent most of my time sitting quietly in a corner of their stall, hoping that if I were unobtrusive, they would get used to me and become less fearful of humans. Sometimes, I sang in a low voice. This approach seemed to work, but only slightly.

When we finally let the goats and sheep into the pasture, their first act was to inspect the fences. They walked to each section of fence, sniffing and examining it. All the while, the farm’s large mare was matching from outside the fence. Then, when the sheep and goats finished their inspection and drifted to the center of the pasture, the mare began running, jumping and snorting. To me, she seemed to be saying Come on! Play! The goats and sheep spent about 30 seconds running and jumping, too, but then stopped. They weren’t comfortable enough to continue.

It would take a few more weeks for our first sheep and goats to feel at ease on the farm. It would take much longer – even years – before all of them would interact spontaneously with humans. But in the meantime, their lives were filled with adventures.

Excerpted with permission from Animal Stories: Lives at a Farm Sanctuary (Lantern Publishing, 2024) by William Crain.