Higher education

During my week at survival camp, the assignments came fast and furious: make a friction fire, build a debris shelter, track creatures of the forest, learn to trap and skin them, cook a fish over campfire coals – and struggle mightily. But the take-home lesson turned out to be singular: remember how it feels to slow down, look around and soak it all up.

Editor’s note: To commemorate the recent passing of Tom Brown, Jr., we are re-posting this story originally published last fall.

It struck me a few days in, what was different. Of course, it was all different – the endless sandscape of the New Jersey Pine Barrens; sleeping in a tent for a week alongside 90-plus strangers; the almost-forgotten feeling of being a student out of her depth, a freshman trying to get her bearings.

But that was not the thing. What was different about the scene in front of me struck me only upon looking through the lens of my camera, maybe halfway through the week. How many of my fellow campers were arrayed around the common area, now captured through my viewfinder? Thirty-four, I counted. And not a single one of them on their phone.

Sure, we’d been encouraged to put aside our phones for the week, but there was no rule expressly prohibiting it during break. And yet, not one person – not a single random lurker in the background – was sneaking a look at a screen.

It was a rare moment of unstructured time, and my fellow campmates were doing all sorts of things: whittling, twisting long grasses into cordage, sitting cross-legged on the ground and talking, standing and talking, walking and talking, consulting a notebook, constructing a mouse-sized snare out of twigs, making a friction fire.

It could have been 1990. Heck, other than a couple pairs of shades perched on heads, some zip-off pants and a Nalgene, it could have been the 60s. What a radical departure from the fidgety, phone-addicted society we’d left behind what, four days ago. That vaguely remembered outside world where on Sunday, we’d parked our cars in a strip mall a handful of miles from here and been shuttled by beat-up van down a rutted sand road into the unknown.

The land before time

I’d had only the fuzziest notion of what I would encounter when I got here. From snatches of overheard conversation, it quickly became clear that my campmates had done a lot more homework. Some clearly saw this week as something closer to a spiritual hegira than an interesting birthday present. (Husband Joe had gone and signed me up for this $800 class as a surprise for my 40th, after I’d mentioned Tracker School over dinner one night.)

One Amish guy who didn’t drive had gotten a ride from Kentucky, having grown up reading and re-reading all 18 books by Tracker School founder, Tom Brown, Jr.

For my part, I’d only gotten partway through one of them, Grandfather, before misplacing it. But the near-mythical story of Tom’s spiritual teacher had been enough to whet my whistle.

Stalking Wolf was an Apache scout of legendary skill, an anachronism of a man who spent much of his 90-plus-year life roaming New Jersey, teaching anyone who’d listen the primitive skills that he’d gathered over a lifetime of ascetic wandering, so that the way of life would not die out. It was nearly seven decades ago that Stalking Wolf encountered seven-year-old Tom gathering fossils in a streambed. The poor Piney kid, the son of a boilermaker who’d come over from Scotland, would go on to become Stalking Wolf’s spiritual successor, a world-renowned tracker, and eventually, founder of the Tracker School.

Other than that read, it had been as much as I could manage to gather the gear from the packing list and untangle myself from the responsibilities of working-mom life for a week. That feat alone had required rearranging multiple adults’ lives to assist Joe in covering for me, and inevitably meant missing the kids’ graduations, playoff games, all the end-of-year things I’d watched them work so hard toward.

No, I had not left them behind to be halfway here.

Whatever it was I was going to find at the end of this rutted-out road, I was going to soak it up through every pore. That was my job this week – that, and to sponge up enough of the information tidal wave coming at me to be able to wring a story out afterwards. My tools to that end were old-school: pen, notebook and camera. No recording was one of the few explicit rules here.

It didn’t matter that I kind of hate crowds of strangers. (“God there’s like 90 people,” I scrawled on page two of my journal.) And too bad that I don’t like being forced to stay up late, a fact of which I was reminded when the first night’s lecture on knives – types of metals, blade styles, sharpening techniques, shoot me now – lasted until 11 p.m., after which, we latecomers had to set up camp in the dark.

We were here. We were here for six days only. Whether we had crossed an ocean to get here or popped down the Turnpike, this and nowhere else was where we wanted to be. That was the common bond I shared with these folks – who, I admit, I’d taken to be a rather self-serious bunch upon first sight of the bare feet, tattoos, mullets and partially shaven heads. Now I found myself wondering whether I’d finally found my people.

Free to spend these minutes as we wished, not a soul was scrolling, texting, or otherwise shortchanging the moment. That was the difference between here and outside.

A common ethos, I guess you could call it. Everyone was on the same page. Everyone was present. Settled, was the word that came to mind.

This is not a vacation

It had taken awhile to get here, to this place where I could step back and see the community in front of me as my own. It was day four – two-thirds of the way through our time here – before I was able to stop seeing myself as an interloper whose best hope of making it through the week was to keep her head down... because I’m not good with a knife, with knots, even with primitive fire-making, which I’d assumed, as a pyromaniac, I’d take to. Heck, I’m useless with my hands.

I used to imagine myself the tiniest bit hardcore, but the truth is I’ve been coddled all my life, right along with the rest of civilized humanity, and these six days were going to be a legitimate test of my mettle.

From the start, Tom had disabused us of the notion that we might enjoy a relaxing hiatus from our outside-world responsibilities.

“If you came here thinking you were going to get a week off and sit under a tree with a gray-haired man teaching philosophy,” he informed us that first night, “you picked the wrong vacation.” It sounded vaguely ominous.

‘Staring bullets’: meet Tom

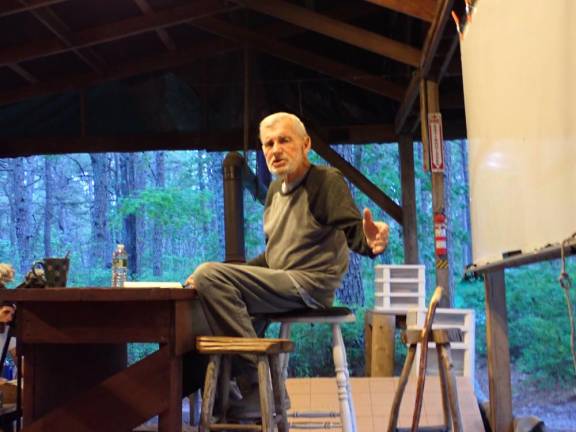

Now 73, Tom is a ropy, stooped but still-powerful man who uses a walking stick and calls to mind Dick Van Dyke in his later vintage. His power, it strikes me, has begun the sap-like process of rising up from his rangy body – which dropped from 240 to a startling 125 pounds after a case of Covid and a fractured spine from a bad fall – to blaze out of his penetrating blue eyes. You don’t need to be a tracker to feel the urgency he radiates.

In his prime, that intensity had been accompanied by a quality of physical menace, we were told, and it was easy enough to believe. “When that man walked into the room, it was like whoa. Like he was going to beat up every single person in the room,” said a longtime instructor.

Now, it’s all in the eyes. “Talk about eye contact,” I wrote in my journal, after one of Tom’s talks. “What he was doing was more energy transfer; soul transfer.”

But his body has been hard-used, and it shows. From the first day of camp, when Tom lectured from atop his three-legged stool, to the last, when he asked his son to bring him a chair, the physical decline of this larger-than-life persona seemed to be progressing in fast-forward. A case of probable food poisoning, was Tom’s explanation for missing the middle chunk of camp to go to doctors’ appointments – something he’d done only once before in 45 years of running the Tracker School, after his dad passed away. But the moment of silence held in his honor before a lecture strengthened the prevailing sense around camp that his ailment was something more than a passing stomach complaint.

Do the work

The fact that I hadn’t gotten much shut-eye the first few nights didn’t improve my disposition. For three nights running I was wakened from a restless sleep at 3 a.m. by the insistent call of the whippoorwill, perched on a branch four feet from my tent, from the sound of it. The nightly audio assault eventually morphed in my exhausted mind, until the bird’s eponymous “whippoorwill” call evolved into a mocking challenge: “Do the work, do the work, do the work!”

Without the warm metronome of my 4-year-old’s breathing to wrap myself around, I felt unmoored, desperate for the oblivion that danced just out of reach. I’d only been away from my youngest for a single night before this trip. I missed my kids to an extent that embarrassed me, so much so that the only person among all these strangers I had any inclination to speak to was 4-year-old Leo, the half-feral son of a pair of the instructors.

This was a crazy trip! Who the hell’s idea was this? Joe’s! Goddamn, Joe, you don’t just go and sign someone up for something like this just because they said it sounded interesting.

So it was perhaps unsurprising that unlike my gung-ho campmates who exhorted the benefits of staying up until 2 a.m. “working on the skills,” all I wanted to do was slink off to my tent, splay face down on my sleeping bag and read the New Yorker.

Four days doesn’t sound like that long, but if you’ve ever lived outside you know that each day is eternal. Here, they had a way of stretching on particularly agonizingly after lunch, as you were sitting in a lecture trying to keep your eyelids from, from...

There is no way to “rest your eyes” subtly in Tracker School. Apparently, skilled trackers can tell by your footprints not only where you were headed and how fast, but also whether your colon was full. To imagine they wouldn’t notice you sleeping 10 feet from the lectern where they stood was on the optimistic side.

Still, what was there to do, short of sticking toothpicks in my eyelids? I was already mainlining watery black coffee.

“I can’t believe dude called me out for falling asleep,” I scrawled in my journal between half-hearted notes on how to secure water in a survival situation. An earnest Aussie instructor young enough to be my son had just made a mortifying reference to my postprandial snooze, and my hackles were up. How I was going to get through the entire week, I wasn’t sure.

Eventually I decided to stop fighting my insomnia and just roll with it. Awakened by my 3 a.m. whippoorwill alarm, I took its challenge to heart. Maybe the bird was actually conveying a message from beyond – everyone said this place was thick with spirits.

Fine, I would do the work. I strapped on my headlamp, unzipped my tent and crawled out into the night. I’d pay for this after lunch, when I wouldn’t be able to keep my eyes open, but there was something I needed to do. I was desperate to get my ember.

Trial by fire

Of the 23 primitive fire-making methods that Stalking Wolf taught Tom, the bow drill is the most reliable and among the easiest. Or so we were told.

Each of us had carved our own bow drill on Monday, turning a cedar log into all the necessary parts: spindle, fireboard, handhold. A solid third of my cohort had gotten a fire going that very day, while I was still trying to wrap my mind around how to hack the log apart without losing a digit in the process. From the frequent check-ins from the instructors (show of hands if you’ve gotten your flame now? And now?) it appeared that grasping this particular skill was going to be the litmus test of success this week.

Even as my classmates graduated to doing it lefty, blindfolded(!), I flailed, my spindle popping out of the tensely wound string, or expending all its frictional energy on making a squeaking noise instead of heat. What was my problem?! I was not accustomed to failing, let alone so publicly, so flagrantly. Worst of all was the advice from sympathetic onlookers (you still haven’t gotten your fire?), which made me want to punch someone.

We’d been advised not to hide out and struggle over the skills in private, but to take advantage of the expertise that had been convened here for the express purpose of teaching us. Personally, though, I vastly prefer to screw up while no one’s watching, and I’d been hankering for just such an opportunity.

This 3 a.m. window was my chance. Finding myself with the luxury of a few free hours, in the privacy of my campsite under the cloak of night, practice in secret is exactly what I planned to do. I would conjure a fire the original way. I would figure it out myself.

I proceeded to give it everything I had: focus, strength, patience, persistence. I push-pulled that bow until I was damp with sweat and trembling with exhaustion; paused to re-carve my spindle points, re-tie my bow string, wave away the moths from my headlamp; and repeat. So it went until the sepia shapes of tree trunks announced the arrival of dawn, at which point I gave it up and went for a skinny-dip in the stream.

My pre-dawn session did not yield a flame – but it did jog an epiphany. Achieving a fire was simply not possible given my equipment. My spindle had gotten too short, as I ground it further down with each attempt, and I’d been ignoring the fact that it had never been perfect to begin with. I could not just muscle through. I needed to stop, carve a new spindle, and then and only then, try again. Two steps forward, one back.

It would be this hard-won lesson that yielded my victory that evening, when my newly carved spindle, with points exactly as described in the diagram, finally spun out enough hot dust to produce wisps of smoke and then a thick, white plume. I folded the ember into my tinder bundle and blew long and slow until it whooshed into flame. I watched it burn a moment, then hustled my baby over to the nearest fire pit. Let my fire live for ten generations! I hollered, giddy with relief.

Grow up

My “trial by fire” had much to offer in the way of instruction. Call it ADHD, call it being a hothead, but I’ve never been long on patience. Did I mention I threw a tantrum on day three of failing to make a fire, stomping my foot and yelling, right there in the middle of that sacred ground?

“A whole lot of nothing!” I practically shouted when an instructor asked what was going on. Nobody said “grow up.” Nobody had to.

Getting down in the dirt like that, being forced to accept that the fire would come only when I had obeyed all of nature’s non-negotiables, was a blow to the ego. Or maybe more of a grinding action. Whatever it was, it left a visceral mark – less on my bruised knees and beat-up hands than in my consciousness.

I’m still a big fan of instant gratification, but my id now shares space with some deeper understanding that you can’t make something happen just because you really, really want to. Sometimes you have to play the long game. You can throw a fit all you want, but frustration is part of the process: a telltale sign that you are bumping up against the limits of your knowledge. That you have some listening to do.

The shuttle out

I was not the only one to struggle, it turned out. It was day three when a couple campmates failed to appear, and upon inquiry it turned out they’d gone home. The angry teenager who worked at a pizza place, whose older brother was recovering from heroin addiction – gone. I’d noticed his starved-looking eyes and half-hoped that he would find his purpose here, maybe become Tom’s next protégé, in the tradition of a long line of troubled souls before him. Nope. And the 21-year-old redhead who talked incessantly about her cats and had never been away from her parents before. Apparently she’d been having heart palpitations.

The loss of our campmates fortified my sense of purpose. Now I set my will against the encroaching I-should-not-be-here feeling: I would not bail. I was here on a mission. It was a vague mission, but there was something I was seeking, something I needed to bring home for myself and my family. And now, I was seeking it along with this group of people who had been, but were no longer, strangers. I realized now that the loss of any one of us – even the weirdest misfit; maybe especially the weirdest misfit – was a loss to the entire community.

Meanwhile, the forecast had begun to brighten. The food was getting better, for one. The dispiritingly bland breakfast oatmeal was, by day three, accompanied by a toppings bar: almonds, cranberries, walnuts, syrup (of the corn variety but still), nutmeg, cinnamon, salt, butter. I wrote every one of these things down because I was – we all were – jonesing so hard after a few days of taste deprivation.

The crappy food turned out, like most things here, to contain layers of meaning. Coyote teachings, this time-tested method of handing down wisdom through the medium of direct experience, often appear to involve a degree of suffering. The lesson here, I believe, was that in a survival situation, life will be a struggle at first, but as you tackle your needs – shelter, fire, water, food – it’ll get better. Also, you’re not on vacation, so don’t sit around waiting to be served your next meal. Plus, by the time the fish and burgers roll around, you will have earned every delectable bite.

There’s probably more to it than that. There usually is. “You’re dealing with a lineage of coyote teachers,” advised tracking instructor Bill Marple. “So if something looks simple, there’s probably more than meets the eye.”

The things she carried

Maybe the upward dramatic arc of the week was partially by design, or maybe it was just my own struggles working themselves out. But I have a feeling that mostly, I owe my about-face to two bits of Styrofoam and my friend Minerva Muzquiz. Minnie is an ultimate Frisbee friend I’ve known warmly but casually for decades, who had – incredibly – agreed to take the plunge with me when I’d mentioned survival camp after a tournament. She’d brought all kinds of goodies, much of it overflowing from a pair of tote bags – a packing style I found refreshingly beachy and, well, non-survivalesque.

Minnie’s stash included: Dayquil, clutch in my effort to power through a pernicious head cold; corn chips we polished off instantly (had we realized how valuable salt would turn out to be we might have rationed them); a seemingly bottomless bag of nuts (unsalted); the New Yorker I would not have time to read; an issue of Bon Appetit that I could hear Minnie paging through like porn in her tent late at night, especially those first few days when the food really sucked; and an extra pair of ear plugs.

That last item was not on the packing list, but it should have been right up there between knife and flashlight. It was these 15-cent nothings that finally granted me the mercy of a full night’s sleep.

“I wake up having slept a full night, from like 10:30-5:45. What a transformative agent is a full night’s sleep in the woods,” I wrote in my journal on a fresh page to begin day four. “I’m not sure I’ve actually ever slept well outside in my life.”

Once I started sleeping, my sense of humor winged its way back from wherever it had been sulking. At some point, I started laughing. It first bubbled up during the lecture on stalking. One way to cross a ridge without revealing or “skylining” your silhouette, was to carry a bush in front of you, advised the earnest young Aussie instructor.

“I always do that,” said the guy sitting next to me, deadpan. I dissolved, picturing my bearded bench-mate scaling a hilltop carrying – for some reason – a potted palm.

After that, the giggles assailed me at odd times. If it was a crutch against my insecurity, it was an effective one. Somehow, laughing lightened my persistent feeling of ineptitude.

My attitude adjustment was a subtle one. I didn’t suddenly stop feeling that my life was a hollow sham compared to these impossibly capable instructors who were living their unadulterated truth, but gradually it all took on a pitch of hilarity.

The instructor-couple Carmen and Matt Corradino, for instance, had lived out here in the Pine Barrens year-round for four and a half years, during which time, whenever they wanted to cook, they had a rule that they had to start a fire using a primitive method. “Never again,” I wrote in my journal, “will I feel holier than thou for not having a microwave.”

Yes, these people were way cooler than me. So much cooler, it was nothing short of ridiculous.

Paying my dues

I was sore, day four. The pads of my right hand were swollen and tender – a novel injury in my long, illustrious career of getting banged up. The Michelin Man hand was the consequence of having ignored advice to the contrary and attempted to muscle my way to a friction fire yet another way, by pressing really hard on a reedy stem twirling between my hands. Yet again, no dice.

My butt was sore, too. My sit-bones felt bruised as they had when I biked across the country two decades ago, but this time it was from sitting on those hard wooden benches hour after hour. Posture has never been my strong suit; now my back was in revolt. How the hell did everyone else sit at attention all day? Catholic school, explained one man-child with a crew cut and ramrod spine who never put on a shirt. A handyman who seemed to glide around camp on the balls of his bare feet, emanating an aura of good vibes, practiced tai chi. The general populace here just seemed to be glowing with excellent health, like maybe they didn’t sit at a desk chair all day back home in regular life. Madeline, who plays guitar and writes her own songs – picture Joni Mitchell, but crunchier – lives on an off-grid homestead in Canada where she bathes every day of the year in the river. These people were hardy stock, hardier than I.

But despite the soreness – or perhaps because of it? – I woke up on day four feeling like I belonged. I was paying my dues, doing the work, like everyone else. “I wake up knowing I’m not half-in anymore,” I wrote in my journal, before heading down to the creek for my morning swim.

With that simple flip of the switch, my step felt lighter. Instead of awkwardly wondering whether to say good morning to the few people I passed on my walk to the swimming hole, or pass in silence at this early hour – I met their eyes and exchanged a relaxed smile. In their faces I saw my own expression reflected, full of the shared pleasure of being part of this secret society of cold-water-loving, early-rising swimmers on a summer morning.

Stay and fight

The big question I’d been hoping would answer itself this week was that mundane, age-old conundrum: what the hell am I doing with my life?

And it did! The constant niggling I’d been feeling about the direction, the authenticity of my work life had been affirmed – yes, there was indeed something very broken and backwards about “out there.”

But my doubts had also been assuaged, and before me I saw a path opening up. Yes, there definitely was a way to keep doing what I do without losing myself. It was as simple as deciding to do it: to inject joy into my workaday, to allow my “real life” to meld with the professional one, to walk through life like I’d walked to the swimming hole that morning, with extra relish.

The second half of that revelation hit me on the last day, fully formed and surprisingly obvious. Not only is there a way to stay the course with full conviction, there is in fact no other choice. That perpetual siren song – to leave it all behind, to shrug off the heavy burden of responsibility and expectation – is nothing but a distraction. What other option is there but to stay and fight like hell?

Maybe it was thanks in part to the sweat lodge – my first – held on the last night of camp, that I was ready to hear it. Perhaps sitting cross-legged in a sweat-soaked half-trance, my mind wandering dreamlike while my lungs inhaled steam in that pitch black, womblike dome with 100 others, had put me in a receptive frame of mind.

The insight landed during Tom’s farewell talk. It hit home with such vehemence that I found myself, even as my pen was flying through notebook pages to keep up, weeping. Liquid seemed to be coming out of every part of my face; continual swiping with my sleeve was futile. I was sitting up front in the middle, plenty visible from all directions. Never have I ever wept like that in public before – oh well. (Whatever dam broke in me that day, it appears to have broken permanently; I’m a crier now.)

Tom was choking up, too. He was sitting up on stage in a chair, too weak now to lecture from atop his three-legged stool. Even as he pinned us with that truculent gaze, his voice cracked with the emotional weight of the moment: the growing futility of his life’s work, the shred of hope that one of us in this room or beyond might yet carry that vision far enough to “turn the flock.”

“You’ll notice that I teach with a certain degree of desperation,” said Tom. He’s got his “supervan” packed and ready to roll when things get really bad, “because when it hits it’s going to hit hard and frightening,” he said. “Like I said, it’s so very close.”

But until that day, he’ll stick it out on the front lines in New Jersey – the most overpopulated, polluted state in our nation, just about within smelling distance of Newark. “I’m not running away. I’m going to fight to save the earth no matter what it takes. I’m a stubborn bastard.”

What else is there to do, after all? It may well be a losing battle, and it’s probably hubris to think I, or any one of us, can make much difference in the grand scheme of things. And yet, what an unforgivable dereliction of duty to do anything other than keep on trying. I had my marching orders, and already I could feel their weight. I think that was why I was crying.

A fellow camper offered me a hug afterwards, which after a moment’s hesitation I let myself accept and enjoy. Why not? Whatever’s coming, we’re all in this thing together.