Prepping goes mainstream

In an age of increasingly frequent disasters, here’s what a third-generation doomsday prepper wants you to know

Prepping is having a moment in the wake of the [insert disaster of your choice]. But for some people it’s second nature.

“My dad raised us as doomsday preppers,” said Lauren Maresca, of Pine Bush, NY. Her grandfather’s suspicion of the government, passed down over the generations, has manifested itself in descendants who like to be prepared for just about any scenario. “My dad always had a fully stocked basement for a bunch of different, worst-case scenarios and I have done the same,” said Maresca, a mother of two who works with people with physical disabilities.

Though Maresca’s friends call her crazy, and even her husband thinks it’s over the top, much of the disaster prepping she’s been doing is now mainstream enough to be government recommended and funded.

“We want you to get in that mindset of becoming your own first responder, at least initially, for the first 24 hours. Because our firefighters, our EMS, EMT workers, our police officers, they’re all going to be busy, right?” said Master Sergeant Jennifer Caoili of the New York National Guard, who co-taught a citizens’ training in Goshen, NY in January, covering scenarios from active shooter to natural disaster and even post-disaster scammers.

Orange County Executive Steve Neuhaus, who introduced the training, had returned from burning Los Angeles two weeks earlier, where he’d embedded with wildfire response crews as part of the Naval Reserve. He described the scene as an “absolute disaster” and a powerful motivator to double down on disaster preparedness back home. Cell phones weren’t working close to the fires, preventing people from getting evacuation alerts – which turned out to be a life-or-death communication in some instances. “We need to do what we can to prepare ourselves right if something happens, and give you some basic things that can help you, and you can help your neighbors with,” said Neuhaus. “We want you to leave here tonight confident, not paranoid – like us,” he added drily.

More than half of U.S. citizens perceived themselves as prepared for a disaster in 2023, a jump from the previous two years though not as many as in 2019, according to FEMA’s National Household Survey on Disaster Preparedness. In rural communities that percentage was slightly higher.

Preppers can be wary of attention, fearing that when something bad enough happens to prove them right, they’ll become a target for the supplies everyone now knows they possess. Maresca, too, believes that “humans are savages when hungry and scared.” Our so-so reaction to Covid, which saw its fair share of panic-buying, hoarding and profiteering, did not inspire confidence that we will rise to the occasion when the next calamitous force hurls us out of our comfortable bubbles.

But Maresca also believes there’s a lot we each can do ahead of time to prevent a bad situation from devolving into chaos.

“If everyone had a little bag, they wouldn’t be attacking each other, or breaking into grocery stores or breaking into people’s houses – at first,” she said. By the time things devolve to that point, she plans to be well away from other humans anyway. So, despite some finger wagging from family members, she is happy to share the distilled lessons of a lifetime’s immersion in what-ifs.

Pack a go-bag

The go-bag is the hallmark of disaster preparedness. Pre-stocked rucksacks are available at a click from $36 to well over $1,000, to grab on your way out the door if you have to evacuate in a hurry. Some call it a bugout bag, others a 72-hour survival system. Some people use a rolling suitcase.

I went home from the Orange County training with a black backpack sporting a New York Citizens Preparedness Corps emblem and reflective tape, as did each family attending. Inside was a pocket radio, a plastic drop cloth, duct tape, safety goggles, a dust mask, a whistle, a flashlight, batteries for the radio and flashlight, a 10-liter water storage bag, work gloves, a Mylar rescue blanket and first aid kit.

We were cautioned not to check “go-bag” off our to-do list (those mind-readers!). This was not a finished product but a start, to be personalized and fleshed out with one to two days of food and water, cash, maps and documents.

The Marescas’ much-better stocked go-bags hang in their garage, one per family member and an additional one for the two dogs, alongside four pairs of hiking boots. For my visit, Maresca unpacked the contents and arrayed them on the dining room table, and typed up the list of items.

The food stash consists of “easy protein” like energy bars, nuts, dried fruit and military rations called MREs (meals ready-to-eat), along with reusable water bottles.

The survival gear looked exciting all laid out, like someone was about to hike the Appalachian Trail end to end. There was an emergency tent; lighter and matches along with dryer lint as a fire-starter; a Swiss Army knife; a tub of batteries and a rechargeable battery pack; water filter; poncho; duct tape, solar charger for phones and small appliances; wipes and bar soap; bug spray; sunscreen; a compass; a camping stove, pot, spoon and collapsible bowl plus extra butane; a deck of cards; paracord; a toothbrush, toothpaste, painkillers and feminine products; electrolyte powder; walkie-talkies that can reach up to five miles; a crank radio; face masks and, usually, gas masks – but those she lent to a cousin who lives near the Greenwood Lake wildfires of last fall and hasn’t gotten them back yet.

Alongside the go-bags, Maresca keeps a duffel with three sets of seasonal clothes per person, to be tossed in the pickup. Another two weeks’ supply of dry food – oatmeal, soup, chicken and tuna pouches, pasta – is stored in an airtight bin, in case they have to camp out. A Ziploc of documents like passports and birth certificates stays in the safe along with cash, ready to grab and go.

The go-bags for the kids, 11 and 3, contain favorite snacks and a card game. “The adults are going to be panicking; you don’t want the kids to be panicking,” she said.

MREs are flying off the shelves at Platoon Army and Surplus in Stroudsburg, PA. “We’ve been selling tons of them. I just had to order a new stock in yesterday,” said owner John Tremper. Designed by the U.S. Department of Defense in the 70s, MREs are more popular than dehydrated or freeze-dried meals because they don’t require water to prepare, he said. In a survival situation you need your water for drinking and hygiene.

“You can eat ’em right out of the bag, heat ’em up in the microwave or on the campfire. I’ve warmed ’em up on the manifold of my truck in the woods.” As for shelf life, “Honestly there is none,” said Tremper, who says he once ate a beef ravioli and meat sauce MRE that was 27 years old. He’s also been selling custom- made bug out bags for $225 containing everything needed to survive in the woods except food and water.

One thing is so obvious it didn’t even get a mention on Maresca’s extensive list, but on the hierarchy of emergency supplies, “Number one is a cell phone charger,” said Master Sergeant Caoili. “My kids probably have like, 17 cell phone chargers, so we’re good on that end. But you want to make sure that your cell phone is charged, and the reason for that is it’s our communication device, right? It’s our news. It’s where we get our information from. It’s also a flashlight, so it dupes as one of your emergency tools.”

If the power is out, you can use a car charger, solar charger, even a battery pack charger that these days can come on a keychain, said Caoili.

But what if your cell phone doesn’t work? We’ve seen it happen here. Cell towers’ backup generators failed about 12 hours after Hurricane Sandy knocked out power in 2012, recalled Neuhaus. The Northeast blackout of 2003 took out power, and swaths of cell service along with it, from New York City to Canada. “That was crazy, but it could happen, and we just have to make sure that we’re ready for that as well,” said Caoili.

Have a plan

Maresca’s plan is to get out of Dodge. Along with her husband and siblings, “we all know that God forbid something bad happens, we’re all headed to my dad’s.” A retired elevator mechanic, her dad lives on 80 acres in Westtown, NY, where he built a house up on a hill with an excellent vantage of the surroundings, with doomsday prepping top of mind. “That’s what my dad always told us, was his worst fear was not a natural disaster but the people afterwards. I don’t want to be here. Even though I’m kind of in the country, I want to get away from people.”

Maresca’s sister, who lives nearby, also has walkie-talkies – though they don’t quite reach from one house to another, they come close. “I would love to get hamm radios that travel a lot further than that but everything’s expensive,” said Maresca, who estimates she’s spent $1,000 on prepping gear.

If you take off, leave a note somewhere obvious like the fridge, she advises, so that if someone came looking for you they’d know where you went, even if it’s coded (“Plan B,” say) so that strangers couldn’t understand.

Sit down with your family and pick two meeting places, advised Caoili: one right outside the house, like a neighbor’s, and one outside the neighborhood, like a diner. These are the places you’ll go if you have to evacuate or you can’t get home because of, say, downed wires or flooding, she said.

This exercise can seem borderline ridiculous when you attempt it with an eye-rolling preteen or a kindergartner with a short memory, but if cell phones don’t work, there might be no way to communicate with loved ones in real time.

Having a family emergency plan tops the list of recommendations – both the government’s and Maresca’s. “That’s the scariest thing to me, if we lose power by terrorist attack or Mother Nature,” said Maresca. “The grid going down doesn’t seem like, oh that’s going to hurt you – but it will,” she said. “You have to realize we’re not going to have gas because gas pumps won’t work, no cell service, no lifesaving devices, water wells, heat in homes that don’t have a fireplace, grocery stores will be down and food will rot.”

Among Maresca’s top concerns is an EMP (electromagnetic pulse) attack, in which a powerful wave of energy causes a voltage surge that takes out critical infrastructure. It may sound far out, but it’s among the scenarios that Orange County has trained for, Neuhaus said. Your car may not even work in that scenario, he added.

Faraday or “go dark” bags that block electromagnetic fields – like the backpack that United CEO murder suspect Luigi Mangione carried – are emerging as a civilian accessory, partly for their ability to protect devices from getting fried by electrical overload.

Stock up on food and water

Go-bags are great if you’re evacuating, but nine times out of 10, you’ll end up sheltering in place in this area, said Caoili. “We stay where we are, we wait out the storm.”

That’s why Joe Tarbell, owner of Richard’s Military Px in Port Jervis, NY, calls the bag he keeps with him a “get-home bag – it’s the gear that gets you home,” he said.

Maresca plans to bug in at her dad’s, but in case her family gets stuck at home, they have a home generator and a section of the basement devoted to a shelter in place scenario. Their long-term food stash includes bags of beans and rice, iodized salt, about 40 gallons of water, a water filter for cleaning water from the nearby stream, and so many canned goods that her husband, Town of Mount Hope Police Chief Michael Maresca, recently made her donate most of them, she said with a laugh.

Some she brought to her dad’s. Most went to people displaced by Hurricane Helene in North Carolina, which she felt good about. Donating periodically is a good way to stay ahead of expiration dates. Now she’s starting to stock up again. “Get things that you a) like to eat and b) that are easily prepared. If you have canned goods, make sure there’s something in there that’s enjoyable. It’s already going to be a stressful situation,” said Caoili. “Don’t just stock up on 40 cans of green beans and say, ‘Okay, I’m done,’ right? Nobody likes green beans anyway.” And if you’ve got cans, she added, make sure you have a manual can opener.

A less-standard item in the Maresca cache is a six-pack of potassium iodide tablets, which protect your thyroid from nuclear radiation. Her husband is of the school that, come a nuclear attack, he’d rather go quickly than suffer, said Maresca. “But I have it because it makes me feel better,” she said. “I just want to feel I have some sort of chance to protect my kids.”

She fills used laundry detergent jugs with water, for flushing toilets in case there’s no running water, another habit that drives her husband crazy. New York State recommends being prepared to shelter for seven to 10 days; Pennsylvania three days or longer. The author of A Navy SEAL’s Bug-In Guide recommends stocking three months’ to a year’s supply of food and water. There is no single standard for advice when it comes to surviving an unknown future.

Build community

Maresca’s decision to invite a stranger (me, and through me, you) into her home with camera and notebook flies in the face of the prepper’s orthodoxy of silence. After all, prepping has emerged in the popular imagination leading with its unfriendly edge, heavy on the ammo, the lone wolf in his end-of-days bunker.

But there’s a greater logic in play here. When it comes to preparedness, there’s strength in numbers. Maresca wants to parlay her knowledge to help other people prepare – not unselfishly, she notes. “I think that the more someone’s prepared the less panic there’ll be, and the less panic helps me, too.”

Though they rarely make headlines, every disaster brings with it stories of neighbors helping neighbors. Residents of an apartment complex used inflatable mattresses to float kids a mile to safety during Hurricane Matthew in North Carolina in 2016. Households with solar capacity shared energy after Hurricane Fiona struck Puerto Rico in 2022.

Scientists are actually now studying the phenomenon of “social capital.” Knowing and trusting our neighbors, it turns out, is critical to our collective capacity to roll with the punches. In a five-day emergency, local sharing drastically buoys a community’s ability to function in isolation, according to the study “Untapped capacity of place-based peer-to-peer resource sharing for community resilience,” published in 2025 in the journal Nature Cities.

Neighbors were well-equipped to help one another with food, medication, first aid, warmth and transportation; less so with power and water, which were in short supply in the communities studied. The more social ties per household, the stronger the protective effect.

Keep your car gassed up and ready

Like many a mom-mobile, Maresca’s pickup is always stocked with blankets, snacks and water bottles under the seats.

She’s working on filling her tank before it gets low, to avoid getting stuck on empty when disaster strikes. “I’m bad at this,” she said. “Every night or whenever I think of it, I’m trying to fill up whenever I can.”

Of all the scenarios that come to mind when you think disaster – wildfire, hurricane, social unrest, drought, pandemic, terrorist attack, government coup, active shooter – the likeliest form it will actually take is car trouble: a disabled vehicle, a car accident, an empty tank on a sub-zero night with kids in the car. Having at least half a tank of gas “gives yourself that buffer,” said Captain Kyle Kilner, a New York Army National Guard officer and Fort Montgomery volunteer firefighter who co-taught the citizens preparedness training.

“Now active assailant, big bad scary, but I do like to preface that in 2023 there were approximately 300 fatalities nationwide from active assailant situations, and there were approximately the same amount of automobile fatalities in New York State alone,” said Kilner. So if you’re going to do one thing, focus on your vehicle, he advised. That means being anal about little things like investing in good tires, checking your windshield wipers and fluid.

Some people keep their go-bag in the car. Others forego the bag and throw a flashlight, first aid kit, duct tape, water bottle and mixed nuts in the trunk and a multi-tool in the glove compartment and call it a day.

Know the backroads

“I know how to get to Westtown from here without touching a highway,” said Maresca. “Try and avoid highways, stick to backroads, have that planned out. In these crazy situations, people panic and the highways stack up.” Videos she saw of people trying to flee the Hawaii wildfires in 2023 – trapped in their cars, choking on smoke – served as a haunting reminder of the importance of both gas masks and backroads.

Maresca keeps maps of New York and Canada and a U.S. atlas in her glove compartment. (AAA sends free maps to members upon request.) Some preppers print or take screenshots of directions to and from work and relatives’ houses without using major bridges or highways, so that they can still access them if there’s no signal.

Be prepared to defend yourself

“People that do prepping and whatnot also are educating themselves on how to use knives, how to use guns, how to use hand-to-hand combat, whatever,” said Tarbell, owner of Richard’s Military Px, who’s been seeing more customers concerned with self-defense in the past eight years.

Tarbell teaches Israeli Special Forces tactics at Hudson Valley HaganaH in Milford, Pa. The studio offered a first of its kind class in March called Be Your Own QRF (quick-response force) that included boxing, self-defense and Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. “The whole concept of this seminar is how to handle your own sh** when sh** hits the fan,” said Tarbell.

Guns could be critical in an extended disaster in which hunger eventually drives people to ransacking, said Maresca, even if it’s to scare someone off with a warning shot. Her husband has a few handguns, an AR-15 rifle and a shotgun in a safe along with about 30 boxes of ammunition, she said. If they have to evacuate, they’ll bring it all. Maresca has learned to shoot a handgun at the range and to load the AR-15.

Whether it’s a gun or a compass, all the tools in the world aren’t going to help you on their own, said Tarbell. “You have to learn how to use them. So understanding how to use a compass, understanding how to use a flashlight in a self-defense situation, or what you can do with your knife to either cut a seatbelt off somebody or cut someone’s pant leg open because they got injured, you know, whatever you got to do,” he said.

Prepping has a reputation as the realm of conservatives and libertarians, but fearing the worst is a growing preoccupation on both sides of the aisle. Groups like Leftist Preppers have been popping up on social media, where members discuss everything from pressure-canning beans to cashing out their 401(k) to the efficacy of pepper gel spray as an alternative to a gun.

After the November election, the Black-led Soul Fire Farm in Upstate New York brought in a facilitator to lead an active shooter response training. The day-long training included identifying campus vulnerabilities and devising a plan for survival, including physically carrying people who are less mobile, the farm announced on social media.

Become more self-sufficient

Self-sufficiency in modern times has “kind of gone out the window a little bit,” said Tarbell, though he thinks people who live in the country have developed that muscle more than their city-dwelling counterparts. “I know people that live in Alaska, and these people, if the power went out for two weeks, I don’t think they’d even notice,” he half-joked. “Everything they eat is what they shot or what they grew, you know. Not that you want to live off the land like Rambo. I mean, I don’t want to do that, but just be able to handle any situation that you come across.”

Stocking up on water and bullets is easy; regaining some of our lost self-sufficiency is by far the most ambitious aspect of prepping. Maresca has made strides down that path, keeping a kitchen garden and a flock of six chickens (down from 10). “The garden right now is smaller, but just I’ve been so busy,” she said, as her three-year-old bopped in and out of the room.

Her cache includes enough vegetable and herb seeds to start a small farm. She’s tried foraging in the woods behind her house without much luck, but there are plenty of raspberries around her dad’s place, she knows.

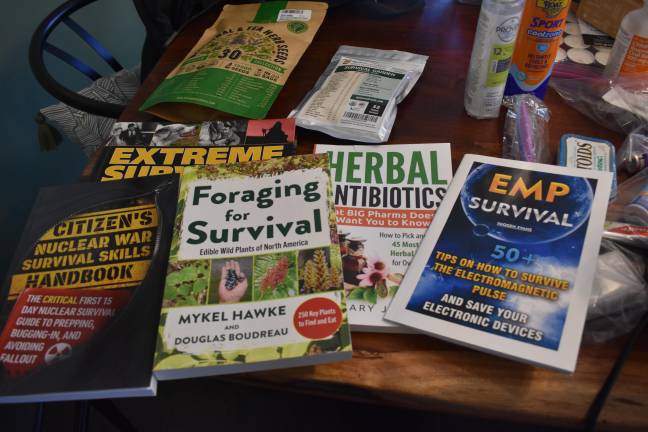

In case there’s no internet, she has amassed a small reference library of books on foraging, herbal medicine, surviving nuclear war and an EMP attack. “I realize how dumb we are as humans. Now we don’t know how to survive without Google,” she said. “I don’t know how to gut a deer. I should learn.”