Eternal vigilance

A legendary activist takes leave of the Clearwater crew after five decades – but not to retire

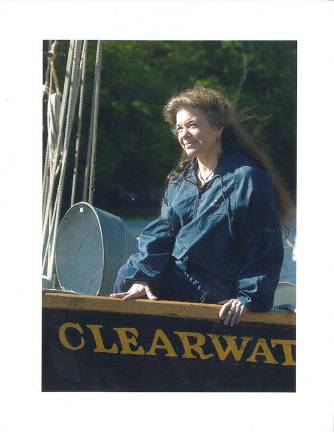

After five decades cleaning up the Hudson as environmental action director of the Clearwater, Manna Jo Green, 78, is taking leave of the famed sloop – not to retire, but to widen the focus of her life’s work to the mother of all problems: the mounting threat of global climate change.

When we talked on June 7, the region was swathed in orange smog, as smoke from Canadian wildfires blanketed the valley. “Unfortunately, we’re going to be seeing more extreme weather events and droughts and floods and fires,” she said. “So the work is even more important 50 years later.”

How did you get involved with Clearwater?

I’ve been active with Clearwater since I was a teenager. I worked as a volunteer at the Great Hudson River Revival, Clearwater’s big, annual festival. I was a litter picker... if you see people picking up litter, it discourages other people from littering. But also, they did public recycling – and I just thought that was so amazing.

At the time – well, first I was raising my family – but then I was also a practicing critical care nurse. I was so enthusiastic about what I learned at Clearwater that I ultimately became Ulster County’s recycling coordinator, and we took our recycling rate from 4% to 40% in a decade.

What’s the secret to getting people to recycle?

One is to make it easy. We distributed, I think it was 165,000 blue boxes so that people would have a place to put their recyclables. And we did a lot of education on how to prepare everything so it was clean and marketable, and the haulers had to pick it up at curbside, or people could bring [recyclables] to a drop off center.

But what I found was, the people who were the most resistant in the beginning, like “Don’t tell me what to do,” “It’s not important,” and whatever their resistance was – once they started practicing and seeing how relatively easy and accessible it was, they became our best and strongest supporters.

What sparked your interest in environmentalism at such a young age?

I became an activist in the civil rights movement. At age 18, I helped form and was the secretary for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) Bridgeport Chapter. And the people that I worked with seemed to have a strong environmental ethic, even though our primary focus was on social justice and equity and civil rights.

I literally wrote a letter on a manual typewriter and sent it to James Farmer, who was the founder of CORE, to ask him to ask Dr. King to come to Bridgeport to help build up our chapter. We were, you know, a couple dozen people. Dr. King accepted the invitation, and when he came we had 600 people come out to hear him, and we were a force to be reckoned with after that. We organized busloads to go to the original March on Washington, etcetera... Caring about civil rights put me in touch with people who also cared deeply about the environment.

Is there one accomplishment that you’re most proud of over the course of your career?

Oh, that’s a tough one. Well, I think seeing the Civil Rights Bill. I actively lobbied for the Civil Rights Bill, and I think that may have had the most far-reaching effect, although there’s still so much work to be done.

At Clearwater, I would say there are two. One is getting EPA [U.S. Environmental Protection Agency] to get General Electric to clean up the PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) in the upper Hudson, and now they’re actually looking at what may or may not need to be done in the lower Hudson.

And the other is getting Indian Point closed and now ensuring the safest possible decommissioning, because as you may be aware, Holtec is planning to discharge a million gallons of radioactive water to the Hudson River and we’re doing everything we can to prevent it.

You’ve spent decades working to get the Hudson cleaned up – and now, again, a company is trying to dump toxic waste into the river. Does it feel like the work will never be done?

Since the passage of the Clean Water Act, we have tools and other legislation so it’s less of an uphill battle, but it is ongoing. Isn’t there a quote that says, “the price of liberty is eternal vigilance,” or something like that? That’s true about the environment.

There are what we call emerging contaminants that were not prevented by the Clean Water Act, and we have to go through a process to add them to the list. For example, in the city of Newburgh... their reservoir is Lake Washington, and it is contaminated with a substance called PFOS [perfluorooctane sulfonic acid]. A firefighting foam that contained PFOS washed into a local pond, and then into the various streams and emptied into Lake Washington and contaminated their drinking water, but it was years before it was found. And people were drinking contaminated water.

We’ve had a bad policy of assuming that chemicals are innocent until proven guilty. We should really reverse that, to think that chemicals can be contaminants until proven safe.

You’re also chair of Ulster County’s Energy, Environment and Sustainability Committee. Do you plan to leave that post?

Absolutely not. Those are things I’ve worked on for a lifetime, so it’s very appropriate that I serve as chair. There’s also a Climate Smart Committee and I chair that as well. Climate change is a great threat not only to the Hudson River, but to all of us in the whole ecosystem. So I am going to continue. I run unopposed, and I think that’s partly because I have a very collaborative approach. Like I learned from Pete Seeger, one of his most important quotes is to learn to speak with people you disagree with. And by keeping those conversations going in a solution-oriented way, I think that’s how we’re going to be able to address the global climate crisis. So I’m not about to give that up.

What do you like to do in the little downtime you have?

I have a wonderful grandson living in a building at the back of my property, who’s five years old and he already has his own waders, and he goes into the little stream, using a strainer to pull up salamanders and tadpoles. Family has always been important, and a source of work, but a source of joy.

I used to spend a lot of time dancing. I don’t dance as much anymore, but I do like kayaking. There’s something very special about being able to move through the water so quietly that the wildlife doesn’t see.